(Hit Ctrl+ to read this journal entry).

Here’s the piece I was listening to as I wrote this:

You can read more about Quiquern here.

Seeking balance in a chaotic world

(Hit Ctrl+ to read this journal entry).

Here’s the piece I was listening to as I wrote this:

You can read more about Quiquern here.

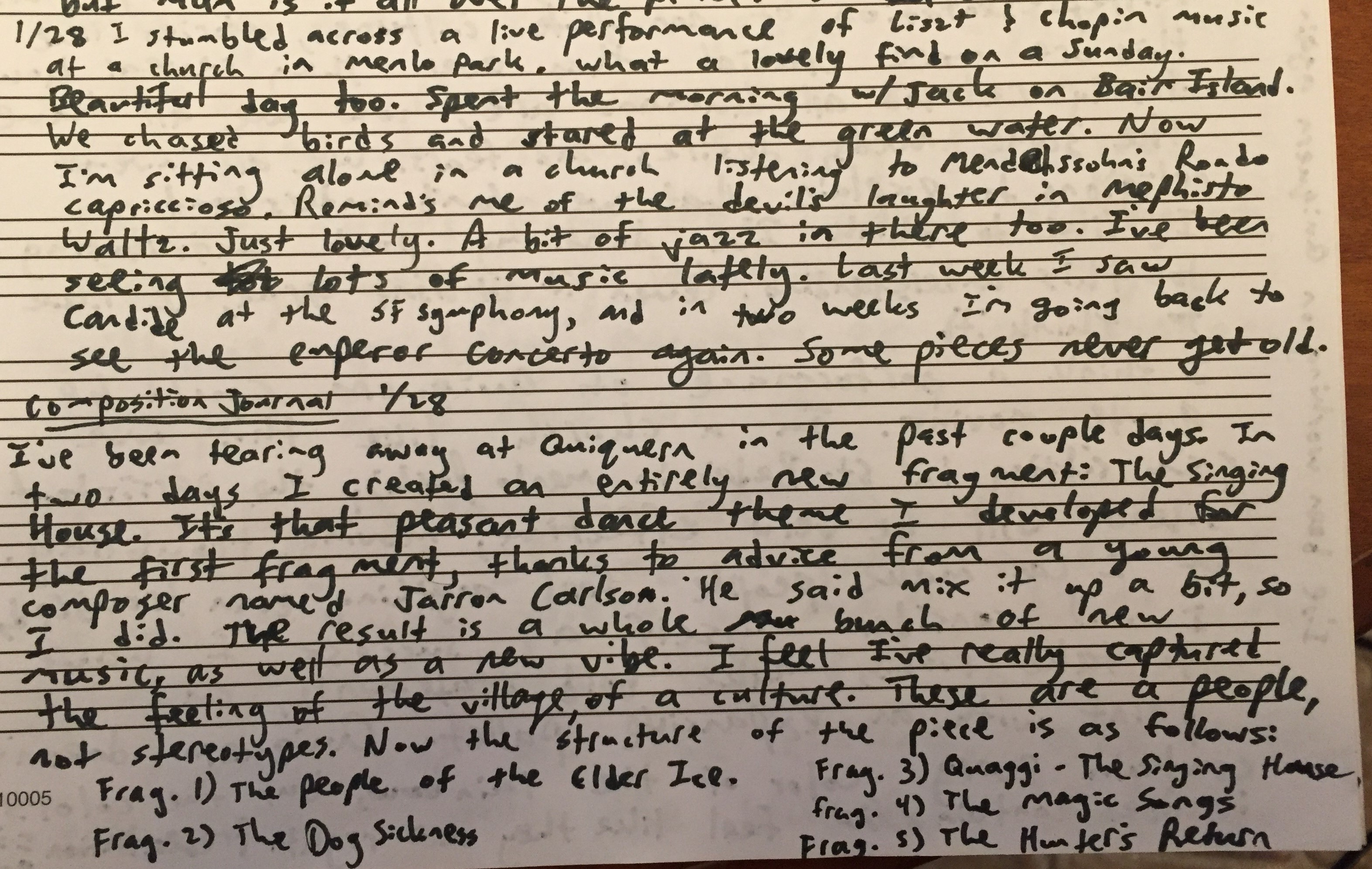

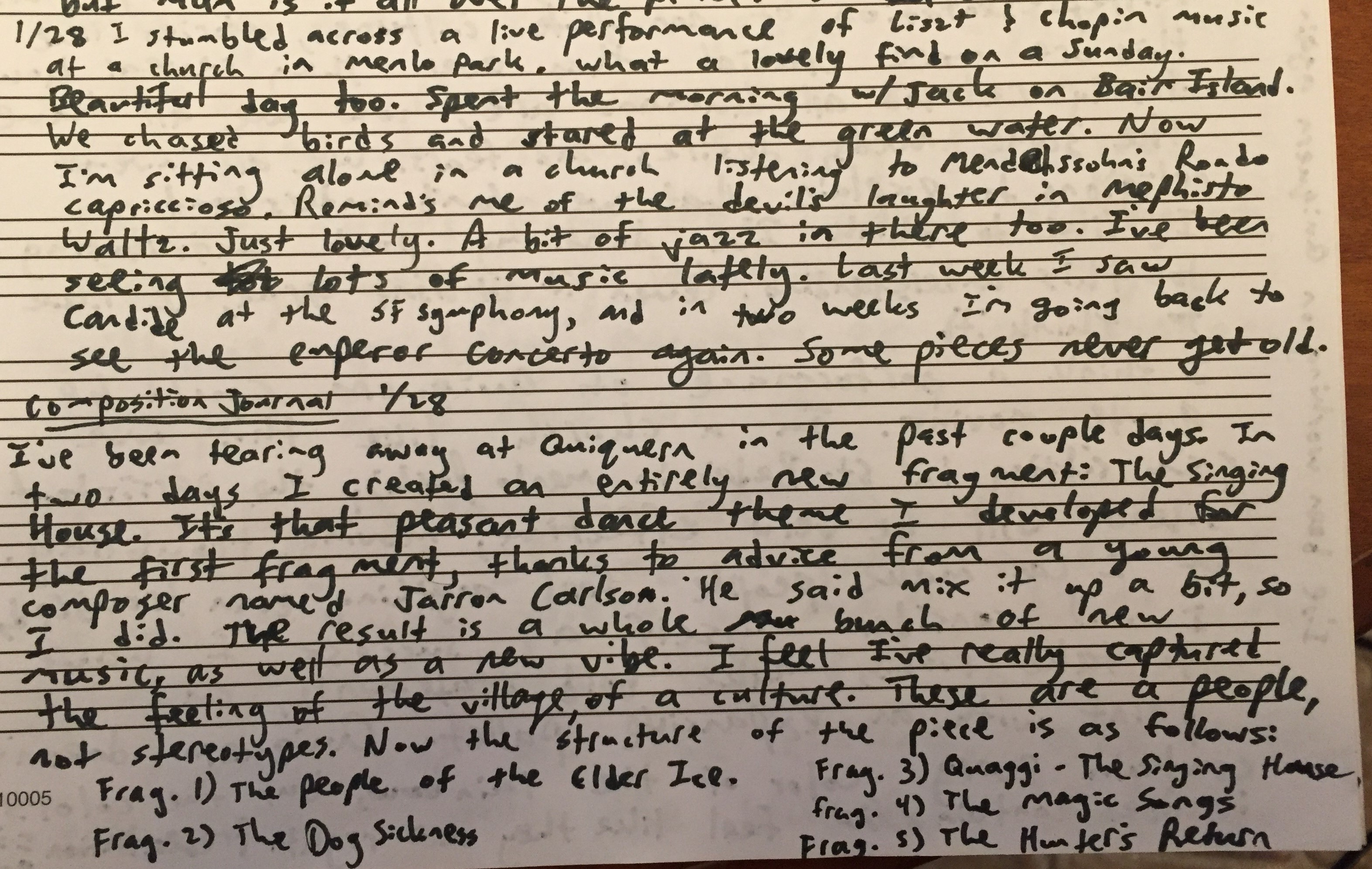

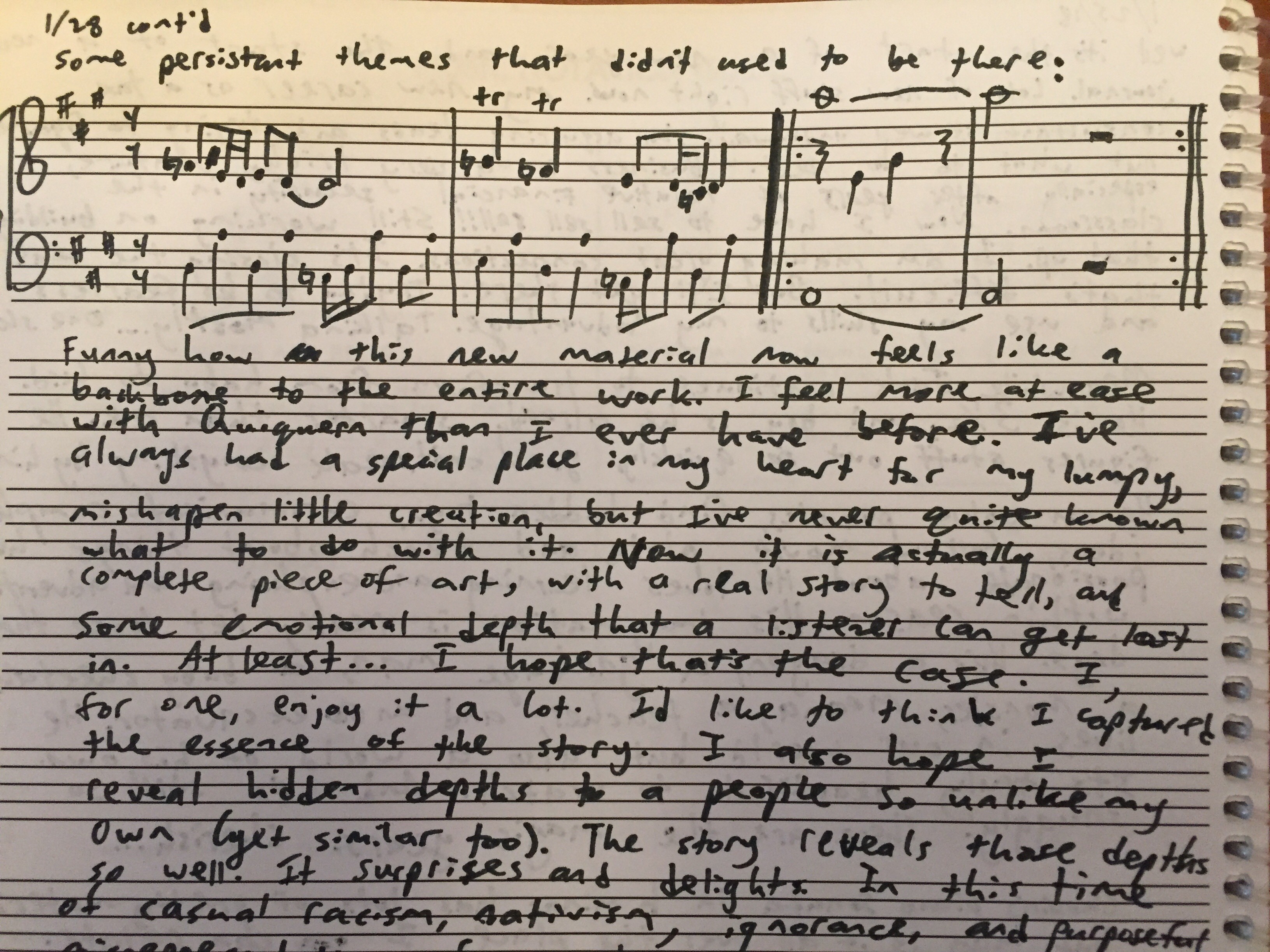

Today I finally completed part two of my piece called “Quiquern.” This movement is called “The Dog Sickness”. (Click here for part one).

I thought “Quiquern” was complete years ago. Time and again I would declare it officially finished. But then, months later, something just wouldn’t sit right with me. I’d pry it open again and tinker with its innards. Maybe it will never be done. Maybe I’m destined to dance with this score til the end of my days.

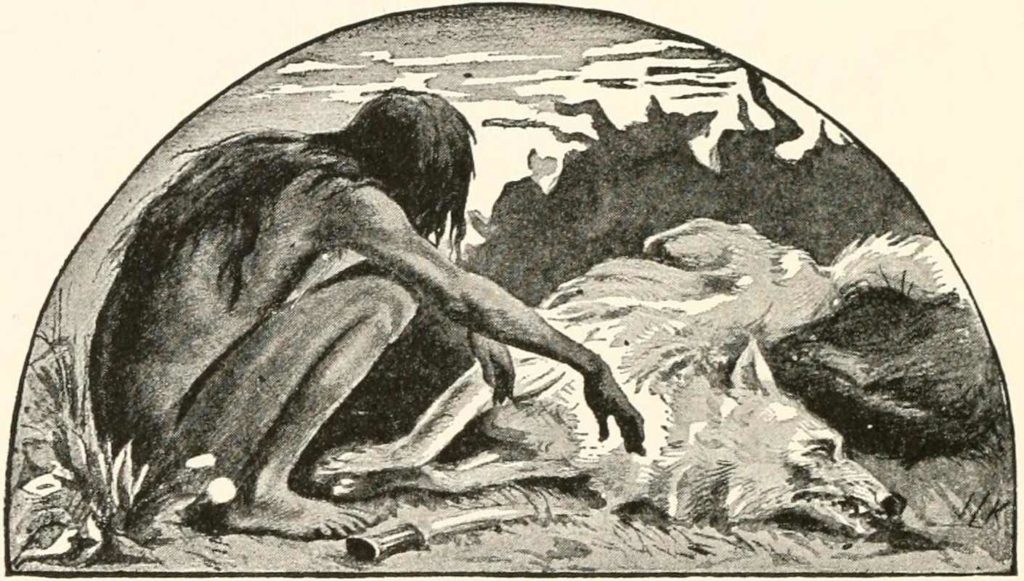

Don’t get me wrong, I have always loved this music. Every time I pick it up again, I’m reminded of why I have such a sweet spot in my heart for “Quiquern”. It evokes so many positive memories: of writing it over Christmas break in San Diego, of reading The Jungle Book over and over, of experimenting with new sounds (new to me anyways), of unhinging my creativity from purely classical harmonies and letting go a bit. Like this sort of thing:

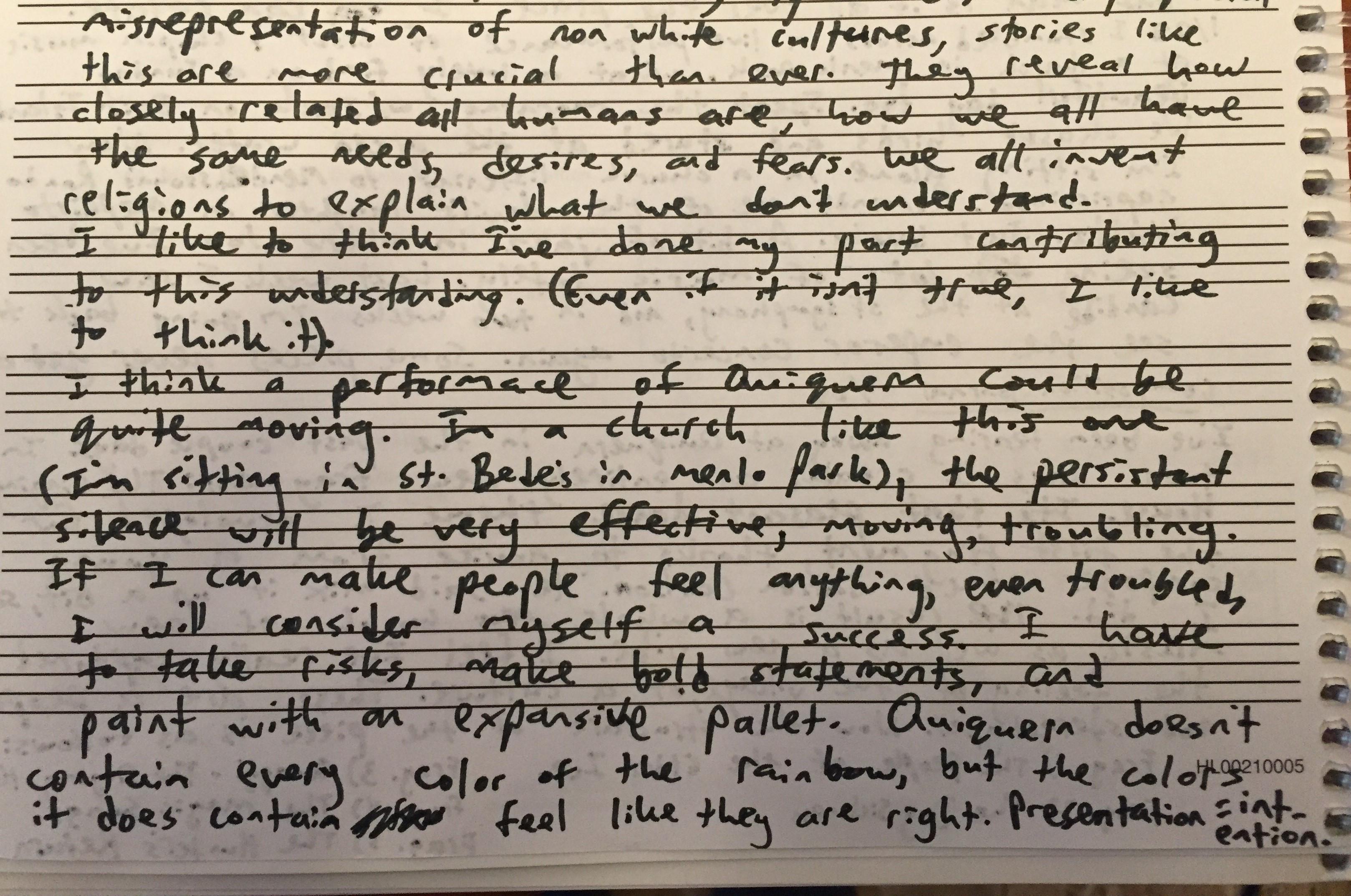

I never go full atonal, I’m always chained in some way to classical forms and progressions, but this piece freed me up in some ways I had never tried. I went wandering a bit through the cold wilderness. I let the images in my mind solidify into a color palette. I focused on the story the sounds told, rather than fussing about the progression. This allowed me to express all the pain I felt after reading that beautiful, heart-breaking story.

So why, if this music was so compelling, couldn’t I call it “complete”? Well there were a few reasons. One is I just wasn’t thinking about form when I first wrote it. I was in “crank it out” mode, writing down whatever ideas popped into my head. I tried to free up my creative process and stop self-editing as I wrote. As a result, the music flowed pretty freely out of my brain, and the harmonies were weirder than I was used to. The musical nuggets that emerged were captivating and exotic. But there was no overarching shape to the piece. It was just idea after idea, with very little connectivity. Throwing a bunch of nuggets into a pile don’t make it a whole chicken.

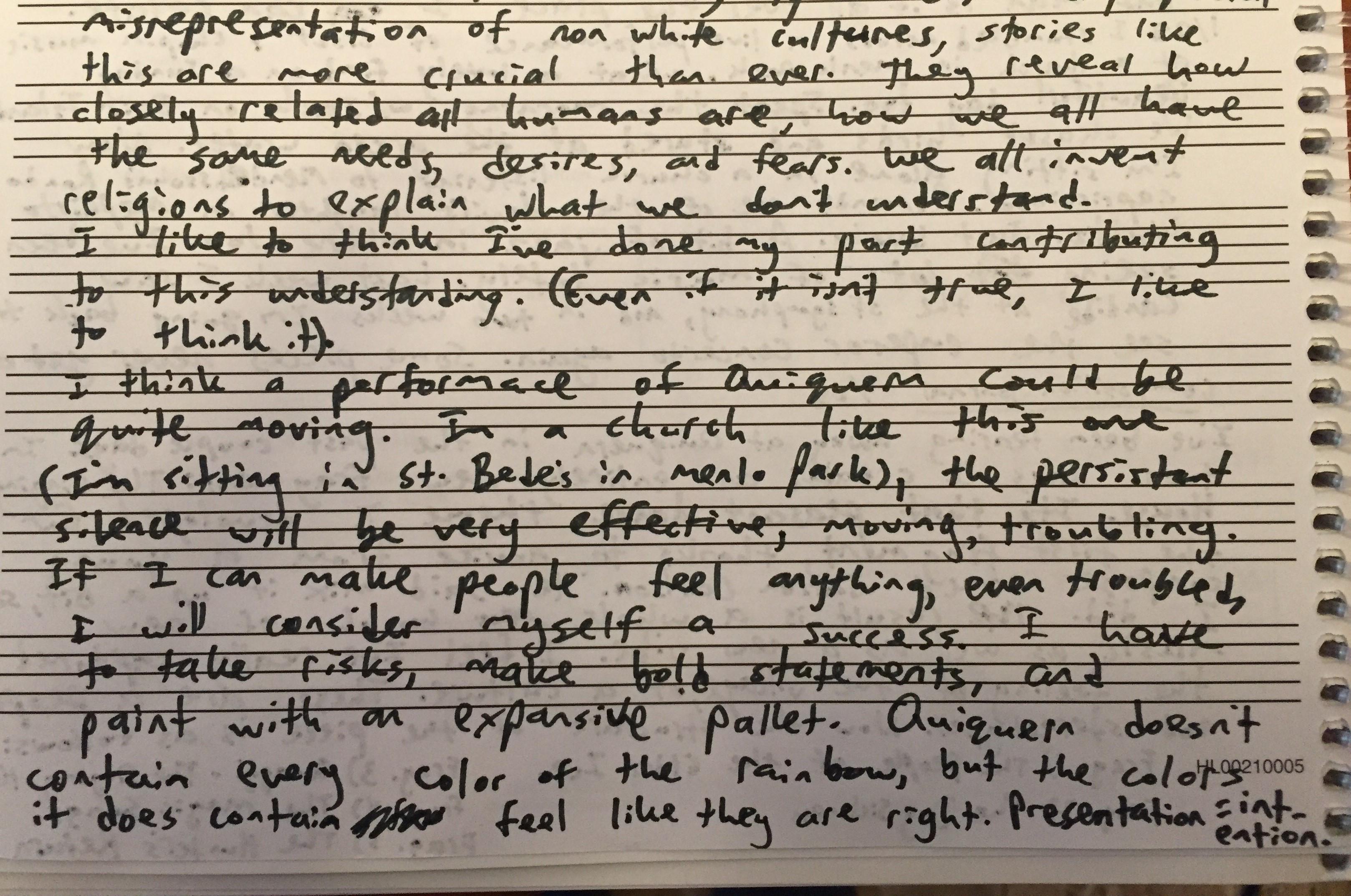

This time around I wanted to work on that. This is the sort of pre-thought that Schoenberg went on about. In other words, real composers think about form and structure BEFORE writing, they don’t just wander around in the dark hoping to bump into a complete form. When I put some thought into this piece, I was able to picture the arc that I wanted to create with the music. A chaotic, hallucinogenic dream sequence, sandwiched on either side by a poignant but solitary theme calling out in the dead stillness of the ice-fields. Perhaps the middle is what the dogs feel as they begin to starve, giddy and terrified and angry; the beginning is what the Inuits feel watching their beloved animals suffer in the dark, knowing what awaits them if another source of food is not found soon. Or maybe the beginning is a song for a way of life that is slowly dying.

Prayers to a cruel and fickle ice god.

And while I was working on form, I also put more thought into motifs. This piece has a lot of rich material, maybe even too much. Though I love that there are so many fun ideas in there, sometimes it plays like one of those Beatles songs with too many good ideas but no development. This time around I went through the piece with a needle and thread, and wove my favorite motifs into the very fabric of the piece. In and out they come, appearing and disappearing again, becoming more recognizable with each appearance. Just as a chef might pour a bit of the boiling gnocchi water into the sauce to bind all the flavors together, my goal was to bind all the ingredients of this music together into something coherent (and tasty).

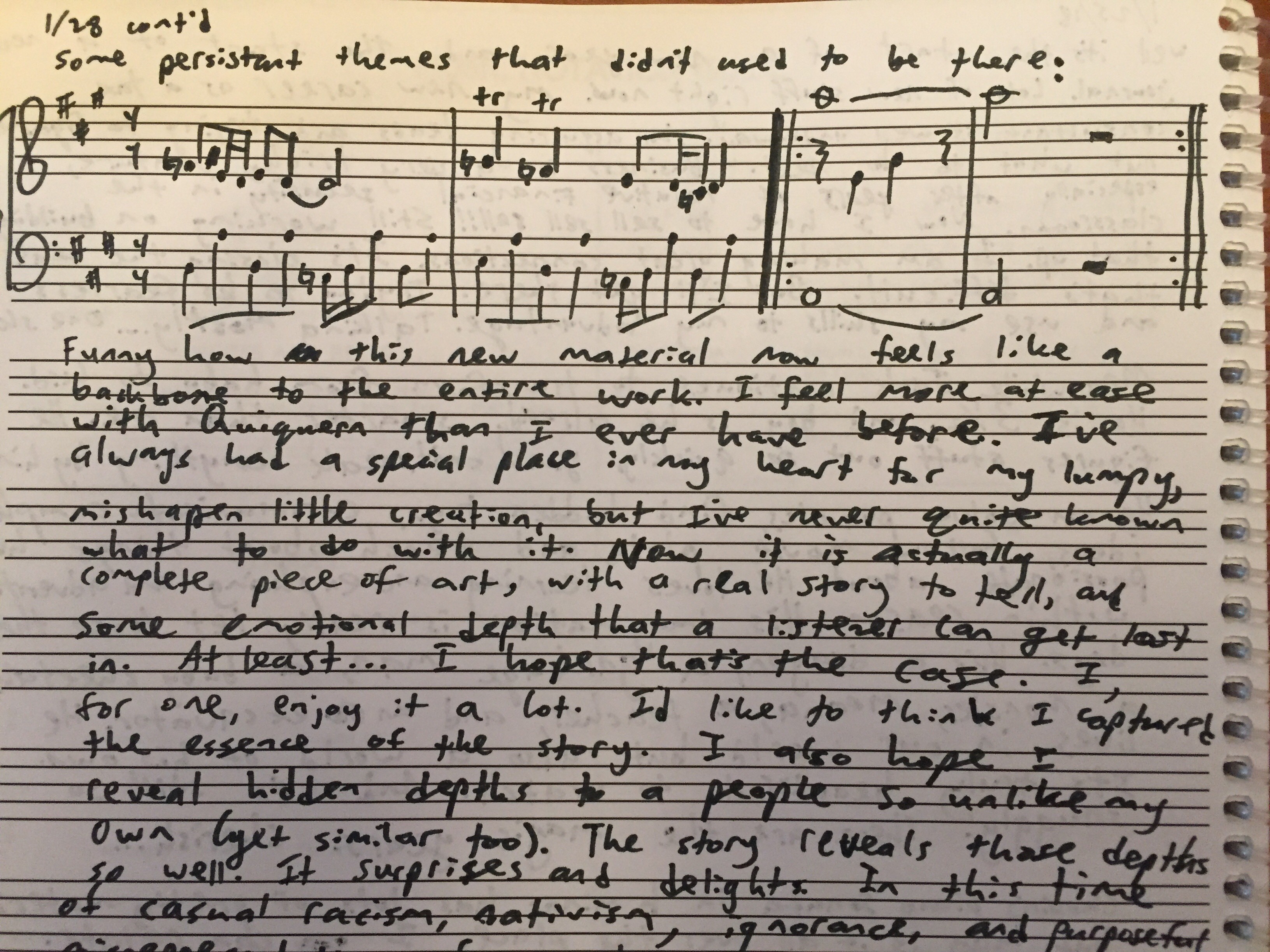

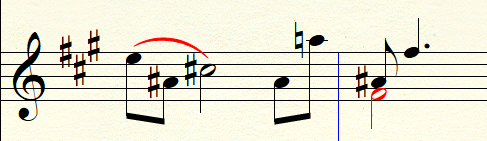

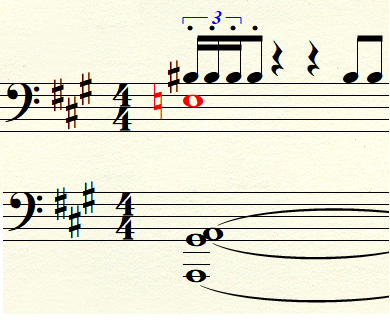

Like this motif, which appears everywhere:

Or this rhythmic motif:

There was something else fundamental that needed retooling: instrumentation. Originally I chose three flutes and piano for this piece, because the flutes evoked the lonely, frozen tundra. But as I was writing, I didn’t pay enough attention to the limitations of the flute. I wasn’t writing in an idiosyncratic way, I was just cranking out music. The used a lot of low C’s on the flute because I liked the sound, but I knew the notes were ringing out stronger in my head than they would on a real instrument, where that low C is easily covered up and lost in the mist. I considered an alto flute, but decided a clarinet would give me a whole other palette to play with.

When one phases in a new instrument like this, one can’t just paste the flute part into a clarinet staff and call it done. The addition of the clarinet changed the whole character of the piece. While the flute is cold and isolated and graceful and metallic, the clarinet is like warm baking bread. It’s also intense, frenetic, a bit insane at times, with low earthy tones that can feel angry or foreboding or subdued. That new voice greatly expanded the range of the piece, so I was able to open the music up a bit and let it breathe.

All these forces combined into something much different than the piece I’ve been kicking around all these years. This version feels like a completed piece of art. It’s not just a sketchbook of ideas, it’s a story arc with real meaning. In other words it really does feel done. For real this time. Seriously.

This music is about suffering, and in a way the audience suffers a bit as they listen. It is not over quickly. But the music is also about hope, and the idea that suffering is a part of life, and doesn’t necessarily cancel out the good. There are joyful memories mixed in with the pain. There is a dream that soon the pain will end. Yes there is fear, yes there is chaos and anger. But the sun still rises at the end, even if the air all around is frigid.