By 1890 the world’s ears had rusted shut. Debussy pried them open with a crowbar and poured jazz down the hole.

When Claude Debussy wrote toward the end of the 19th century that “any sounds in any combination and in any succession are henceforth free to be used in a musical continuity,” he probably did not foresee the likes of John Cage or Lawrence Chandler or even Frank Zappa. Yet even if Debussy might have doubted whether these later composers’ experiments could actually be called music, Debussy was a kind of father to them all. His groundbreaking use of harmony announced to the world that anything was acceptable, that composers could literally do whatever they wanted, that any colors were appropriate in any combination. He broke the rules! But more importantly he gave his successors permission to systematically deconstruct the rules to such an extent that they became like the oxidized old Beethoven statue in Bonn, Germany: a memorial to something that was once great.

The 19th century had revealed itself to be a musical landscape in full bloom, with every major genre of classical music reaching its mature peak. With demi-gods like Liszt, Wagner, Chopin, and Brahms at the reins, harmony and form were stretched and expanded past mastery to the point of decadence. Like old fish in an aquarium, 19th century composers had explored every crevice of the traditional ensembles: string quartet, symphony, sonata. And yet despite the genius of these creators, all of their music was still bound tightly with “rules”. No parallel fifths! Resolve tritones a specific way! Meter ticked away time and did not change, could not change. Rondos and recapitulations and cadential 6-4s became to us like old friends who we never tired of seeing, though we knew every nuance of their personalities. These tried and tested techniques provided a foundation upon which Beethoven had built a mighty cathedral.

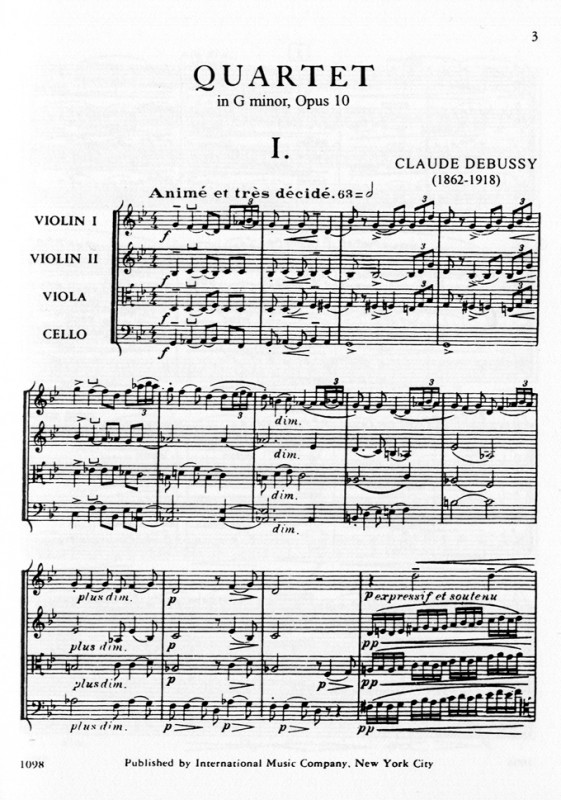

But in the rough emotional seas of the late 19th century, Beethovenian constructions had begun to lose their emotional impact, and sophisticated ears demanded something strange and new, something a bit dissonant, something that bent the ear. Debussy showed composers the way toward this new realm of emotional release. The piano, the orchestra, the soloist, the old forms, the sarabande, even the bassoon all seemed to speak a new language under his spell. Never was this more true than with Debussy’s one lonesome string quartet, opus 10.

It opens as a captive flock of birds peck anxiously around their cage. They become more agitated, and soon the bolts come loose and the cage shatters. Or perhaps the music opens as a flowing river of honey, on which a tiny rudderless vessel is pulled inextricably toward the sea. Or perhaps it’s an old coat worn thin by constant use. Its owner feels naked without it. Or maybe the opening bars reveal Debussy’s rage at having to abandon his forever unfinished opera “Rodrigue et Chimène” the previous year. No matter what it means, the music pulls you up by the ears and places you down somewhere you did not expect.

Listen to the first movement of Debussy’s quartet here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1TYKpgjs-mE

That heavy opening theme appears time and time again throughout the piece, through all four movements. Like sister islands separated by miles of ocean, each reoccurrence of the theme is subtly different from the previous one. On one island clusters of triplets tumble over each other like ants. A musical idea that was angry and threatening a moment ago is in the next moment serene, only to reappear later clenching its fists in fury toward the heavens. Each time the islands appear on the horizon they signal safety, a place of rest. They give the listener a moment of much-needed peace, because like islands these reoccurrences are each separated by many leagues of turmoil and danger. Immediately after the first theme is revealed the music takes flight, diving fast down the wall of a canyon. Seventh chords stand on their heads as the voices layer over themselves like hot fudge. Upon first hearing this section of raw development, the listener may find himself lost in the chaos, alone and map-less. But soon he washes up upon the next island, a world both familiar and foreign to him, one he recognizes as his own except the sun is a different color. And that was Debussy’s specialty: changing the color.

Many composers speak languages all their own. The same year Debussy set pen to paper, Dvorak wrote a couple string quartets too. His music evokes horses galloping across the American countryside in all their pentatonic glory. But pastoral scenery, though carried by Dvorak to an almost divine pinnacle, was really nothing new. His music may sound distinctly Dvorakian (it gushes with melody and fills the soul with a sense of wonder at the beauty of the world), but it’s still built with the same hand-me-down blocks first fashioned by Haydn and Beethoven (Dvorak himself gave credit to “Papa Haydn” for inspiring his music). Even the finale from Tchaikovsky’s Symphony Pathetique, also written that same year, feels like it longs for something deeper. Though the music boils over with liquid emotion and raw hunger, it still claws toward something deeper, a different world, one just beyond Tchaikovsky’s grasp. Debussy’s string quartet may not climb to the same emotional heights as Tchaikovsky’s last great masterpiece, but it certainly lives in that “new” world that Tchaikovsky couldn’t quite reach.

Claude Debussy was the first to show us this unexplored territory, so we will remember his name forever. We will compare him to the other great innovators and bridgers of gaps. As composers we will generate our own new ideas and ask ourselves “What would he have thought of them?” We will borrow his motifs and introduce them to the 21st century. We will place him on a pedestal, discuss him in theory classes, and write his name on the music history timeline of important events. And why not, the man was an artist. His parallel fifths ring through the mist like the bells of a sunken cathedral. His timpani crashes against your head like a good hit during a pillow fight. Listening to “Danses Sacree et Profane” is like having warm paint splashed in your ears. The tritones have been sculpted with such delicacy that they not only sound consonant, but they appear through the haze to be previously undiscovered intervals, alien sounds wholly unknown to the modern world. What a perfect way to usher in that most newfangled and metallic of centuries: the 20th century. Debussy took the chords that theory teachers had been angrily crossing out for 300 years, and turned them into extraordinary art. And he made it look easy, the jerk.