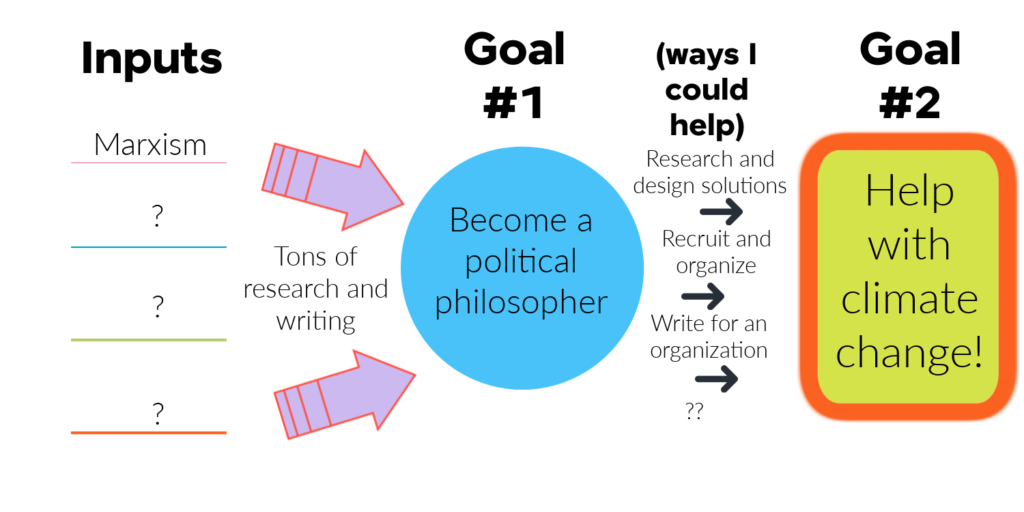

In May 2021 I picked up An Introduction to Political Philosophy by Jonathan Wolff in a book box. Reading that book was like sampling heroin: I was addicted immediately, my brain permanently altered. Twenty years ago I majored in history, but I only ever took one philosophy class, and no political philosophy classes. I didn’t realize until I read this book what a lost opportunity that was. Since reading that book, I’ve read philosophy almost exclusively, and have developed a strong desire to pursue it academically, to study it to the hilt, to become a philosopher myself. For now I consider myself an undergrad. I have so very much to learn, and I’m restraining my urge to write tons of half baked blog posts based on the scanty information I’ve gleaned over the past two years. My job for now is to read and read and read some more, pausing only to process what I’m reading, take notes, think, and build a research library. My particular area of interest is Marxism, specifically to address the question of whether Marxism is at all a useful tool for solving the major problems of our time, such as income inequality and environmental degradation. But before I can form any opinions on that question (or any other), I need to acquire some background knowledge.

Background knowledge I need to acquire:

- The long chain of Western philosophical texts and major ideas that span from the Ancients to today: Plato, Aristotle, Descartes, Kant, Hegel, Nietzsche, Russell, etc., and the political philosophers as well. Also formal logic, philosophy of law, and studies of democracy, liberalism, anarchism, conservatism, and progressivism.

- The major socialist and Marxists thinkers that span from the early 19th century to today: Precursors to Marx, Karl Marx, Engels, Kautsky, Lenin, Trotsky, Lukacs, Marcuse, Althusser, Habermas, etc. I must study all the threads of Marxism before I undertake to analyze, critique, or judge the tradition.

- Modern interpretations of Marxism: humanist, feminist, ecological, democratic, etc. How are they different from older traditions, and what do they have to say about the older traditions? What problems do these new interpretations attempt to solve? Any successes?

- Style guides for academic work, argumentative best practices for works of philosophy.

- The history of Marxist and non Marxist revolutions that have occurred during the last 300 years. What forces motivated them, what worked and what failed, what parties and ideologies came to the fore, what were the results?

Goals:

- Study the history of western philosophy to the fullest extent possible. My goal is not to become an absolute master of the full spectrum of western philosophy, but to develop a foundational knowledge upon which I can build a more specific area of expertise.

- Develop a masterful understanding of the history of Marxist ideas from the beginning to the present, including all the tentacles of this labyrinthine tradition, and where the tradition stands today. This is the critical background information. Along the way, write practice essays on whichever topics catch my fancy.

- Develop specialties within the Marxist tradition, and compose a larger work (a thesis?) that pertains to that specialty. Specialty 1: Leninism and Trotskyism (the intricacies of the philosophy, how it has been applied around the world, why it has failed to achieve its goals, whether it is useful today). Specialty 2: (unknown at this time).

- Develop a foundational knowledge of the international history of revolutions, from the French Revolution to today.

- Construct a thorough and well organized research database that I can tap for various writing projects.

- Build toward a synthesis that combines the lessons learned from a long study of Marxism (including an understanding of the weaknesses of the philosophy and the ways it has failed) and wields them against the intransigent problems of today. In other words, find a way to adapt and modernize Marxism, find and fix the weaknesses, and assess whether the tradition has anything to offer against our current problems, or whether it is a philosophical dead end.

Progress so far:

- I’ve read a some of the foundational works of Marxism and well as some critical commentary on Marxism (including works by Thomas Sowell, David Harvey, and a compilation edited by Terrell Carver. Mostly I’ve focused on Marx, Engels, Lenin, and Trotsky for now, but intend to keep traveling chronologically through the history of Marxism. I consider this a modest start. See my Currently Reading page for titles. I’ve only read these works once, so my understanding of them is that of a student newly exposed to a plethora of difficult and stimulating ideas. Based on this limited first reading, I have started to formulate some embryonic responses which in intend to develop further as I read and re-read these challenging works.

- My readings of classic texts from Western philosophy is even more limited. So far I’ve read Plato’s Republic, Crito, Apology, and Phaedo, and well as Karl Popper’s damning commentary on Republic. I’ve listened to a couple survey courses on Audible as well, but that’s about it. My knowledge of philosophy, especially outside the realm of political philosophy, is very limited. I’m signed up to take an Intro to Philosophy course in the autumn.

- Following the advice of Umberto Eco in How to Write a Thesis, I’ve started a revamp of the research database I’ve been building over the past two years. I am starting to create “index cards” on the app Trello to document my readings and ideas, so that I can organize them use them repeatedly for various writing projects. This will also help me understand better what I actually want to say down the road.

- I have developed some very preliminary hypotheses, namely this:

Marx's critique of capitalism, though slightly dated, still has much to teach us about modern capitalism, and has applicability especially in the face of growing income inequality and climate catastrophe. At the very least it is useful as a set of analytical tools that helps us understand the world in which we live. That being said, his prophesies about the future revolutionary collapse of capitalism and abolition of alienation appear both idealistic and far-fetched, very different from the materialist, scientific criticism of capitalism that he developed over the course of multiple decades and presented so forcefully in Capital. So to summarize: Marx’s critique useful, Marx’s prophesies not so much. Later, Vladimir Lenin mistook Marx's prophesies as scientific proofs, and so dismissed all critics of Bolshevism as opportunists, liars, frauds, charlatans, and traitors. Armed with the certainty of a religious martyr (and a certain blindness in regards to the weaknesses and contradictions of his own philosophy), he sought to engineer a utopia via authoritarian tactics, paving the way for all the debauchery and mass murder that defined the Stalin era. One of the key mistakes in Lenin’s approach was his cavalier dismissal of liberal democracy as "bourgeoisie democracy,” and his preference instead for a “dictatorship of the proletariat” that would somehow eliminate all classes, purge out all the capitalist elements (and capitalist people), and then finally dissolve their own dictatorship; the state itself would disintegrate into nothing. And so, through violence and the complete annulment of civil liberties, he would establish mankind's communist utopia. From his safe haven in London, Lenin argued that the very concept of civil liberties was a sham; all the hard-fought progress mankind had made toward the sanctification of democracy was recast as a grand conspiracy perpetrated against the workers by the propertied classes. Therefore it was in the working class’s best interest to abolish civil liberties in order to accomplish their singular goal: the destruction of all classes and the state (Lenin assumes this is the singular goal of all good and honest proletarians). This was a vulgarization of Marxism. Marx understood that the world is a complex place, and his analysis is filled with endless caveats, disclaimers, and footnotes that demonstrate that he did not believe there were any easy or simple solutions to the world's problems, and neither was it useful to categorically blame the world's problems on one single class. Lenin, on the other hand, has no problem pointing out who the enemies are. He paints a grotesque portrait of human history wherein the bad guys (elites, liberals, intellectuals, capitalists, and even the middle class) cheat and swindle the good guys (the workers) out of their rightful inheritance: a world where no man possesses any power over any other man. Counterintuitively, in order to usher in this perfectly egalitarian world, we must first conduct a violent purge of any who disagree with this interpretation, a holocaust of all "bad guys." In other words, if we just murder enough people, we can finally have our utopia. Lenin pulled the lever so hard toward the “idealism” direction that his Marxism, once rooted in a scientific analysis of “the now,” lost touch with reality and forgot what real people are like. In his writings, Lenin seemed to expect the workers to all think with one mind and fight ceaselessly for one singular goal, as if the real life proletariat was capable of embodying the ideal Form of “proletariat” that existed in Lenin’s mind. Lenin's ideal proletariat is incapable of pluralism; they have no differing opinions on matters of economics, government, or human morality. Instead they exhibit a hive mind mentality, and dream only of accomplishing Lenin's own goal: the establishment of perfect communism. These ideal workers will joyfully limit democracy in order to expand it, they will violently seize full dictatorial power in order to one day voluntarily dissolve their own power, and they will nullify civil liberties in order to create a more egalitarian society. At best, these contradictions render Lenin's theories incoherent; at worst, they provide a ready-made philosophical justification for totalitarian government. Lenin's vision of "the people" is highly idealistic. Those who agree with Lenin are “the people” and “the masses.” Those who do not agree - perhaps those who disdain violence in general, or wish to shield their families from war, or voice alternative political/philosophical opinions, or oppose revolution on religious/nationalist/constitutional grounds, or believe that Lenin's narrow road to utopia might contain some potentially catastrophic flaws, or simply hold a different interpretation of Marxism - are not "the people." Since only those who agree with Lenin count as people, many millions of proletarians (the group Lenin claims to speak for) who dissent to Lenin's program will need to be dealt with if the revolution is going to proceed. This will mean mass disenfranchisement, exile, imprisonment, and murder of proletarians. In this way Lenin reveals that, regardless of his claims to the contrary, he cares less about one's class status than about one's agreement with his program. In other words, his version of the "proletarian" dictatorship isn't actually FOR proletarians; it's actually only for people who agree with Lenin. It's a classic one party state - the only thing that matters to the party is that you agree with the party. Agreement with Lenin is the sole real criterion for citizenship; all who dissent must be purged. Thus, "the people" is transformed into "those who agree with the party," which is how Lenin can technically argue that his state is the first state in human history that actually serves "the people" - all persons who aren't part of "the people" are made to vanish entirely. And so Lenin's new idealistic Marxism predictably dissolved into a totalitarian nightmare; permanent single party rule instead of worker democracy, a new ruling elite instead of a classless society, a totalitarian bureaucracy instead of a dissolved state. It was all right there in his writings, clear as day, before he and his clique ever grabbed the reins of power. Today most people blame the disaster of Soviet totalitarianism on Stalin, but Lenin provided it with philosophical grounding, and certainly got the ball rolling during the brief few years he wielded power. There must be a way to preserve what is great about Marxism while discarding what is disastrous in Leninism. Most importantly, a synthesis between democracy and socialism must occur if Marxist philosophy is to outlive the revolutionary disasters of the 20th century. We have to drop the notion that a dictatorial “vanguard party” can ever violently establish a classless society, without themselves devolving into a new ruling elite. Without democracy and civil liberties, Marxism presents a recipe for dystopia. But really this assertion demands that we either abandon Marxism altogether (which I do not wish to do), or find a way to combine Marxism with liberalism, without destroying the essence of either. I believe Marxism may still have a role to play in helping us solve our most intransigent problems, but only if real democracy (not the sham “revolutionary democracy” Lenin promises) plays a key role in the process. Perhaps this amounts to no more than progressivism, or perhaps it will mean more than that. I’m not even close to convinced that it’s possible for humans to transcend capitalism entirely; perhaps progressive capitalism is the closest thing humans will ever achieve to communism, while still preserving democracy. But is modern day progressive capitalism a powerful enough tool in the fight against (capitalism-induced) climate catastrophe? And to question this from another angle, does progressivism actually even lead to increased democratic control over the economy, if the end-result of progressivism is government takeover of industry? If the government is currently run by elites, than transferring ownership of key industries into elite hands doesn't sound particularly democratic either? Is there actually a way to create a more democratic economy, without simply giving in to laissez faire capitalism (which seems to be leading mankind toward climate disaster)? I’d like to explore ways that we can use Marxism (in one form or another) to address the big problems of our time, but I intend to stay focused at all times on the way humans really are in the real world, and keep idealism out of my analysis. I believe that anyone who promises a utopia and a permanent end to human suffering (especially if this goal can only be attained through violence and repression) is either misguided or a cynical, power-hungry opportunist. But I also don't believe that liberal democracy holds all the keys either. No system is perfect, and costs must be weighed at every turn. Ok so that’s my rough hypothesis, as it stands today.