Utilitarianism starts with a basic premise: every person on earth desires happiness.1 Since happiness/pleasure/well-being (I will use these all interchangeably) are universally desired for their own sakes (not desired as means to some other end, but desired for themselves), they must be intrinsically good, i.e. good for their own sakes, as opposed to instrumentally good.2 If we wish to live an ethical life then, we must aim our actions toward achieving that which is intrinsically good: happiness. This does not mean happiness for ourselves only, but also (more importantly) happiness for others. In fact, it is our moral duty to maximize well-being to the greatest extent possible. If we boil utilitarianism down to its simplest message, it might read: do as much good in the world as is humanly possible.3

Utilitarianism requires us all to look outward, and judge our actions based on how they impact the community of persons affected by our decisions. But often there is a conflict between what the individual desires and what would most benefit the community. In this case utilitarianism issues a direct challenge to the individual: if you desire an end that does not maximize general happiness, you are required to abandon your desire. This turns out to be a very strict standard indeed, one that may require us to make tremendous personal sacrifices for the good of others.

If utilitarianism is supposed to be our guide for living ethical lives, we must recognize right off the bat that most of the decisions we make throughout the day do not maximize general happiness. After all, by taking the time to write this essay, I am choosing not to use that time to serve food to the homeless. Does that mean it is unethical to write this essay, because by doing so I fail to maximize utility? Must I strive to meet the utilitarian standard in all my daily actions? This forceful version of utilitarianism seems to demand that we all become saints, constantly subverting our own desires for the benefit of others. If so, then is utilitarianism even feasible as an ethical theory? If the moral requirement is so strict that normal people are incapable of meeting the challenge, is the theory practical at all?

We all have busy lives full of persons and obligations which require our full attention. Our children, our parents, our spouses, our bosses, and our friends all (rightfully) make demands on our time, leaving us very little bandwidth with which to decipher what “the general happiness” means, let alone time and energy to maximize it. For many parents with young children and full-time jobs, it can feel impossible to do anything for the community while trying to juggle such a home life. Faced with such a complex and intractable dilemma, many people ignore completely the needs of the community, and focus instead on the daily demands of life.

We could attempt to justify such a lifestyle choice (from a utilitarian standpoint) by defining a busy parent’s ‘moral community’ in a narrow way: it includes only her family and friends and colleagues; everyone outside that circle is excluded from the community and therefore excluded from the utilitarian calculus. Does a person with such a narrow moral community live an ethical life? Is it ok to define one’s community so that it only includes those persons one is actually capable of serving while still living a “normal” life? Or must a person restructure her entire life in order to expand that moral community, i.e. tailor her whole existence around service to the wider world, even at the expense of her own family’s happiness?

Really I’m asking: whose happiness should we care most about? Jeremy Bentham answers: “the greatest happiness of all those whose interest is in question [is] the right and proper, and only right and proper and universally desirable, end of human action.”4 This is famously known as the Greatest Happiness Principle. J.S. Mill, a few years after Bentham, demands (in a statement which contradicts many other statements in Utilitarianism) that our moral standard be “not the agent’s own greatest happiness, but the greatest amount of happiness altogether.”5 Seems clear enough. But for the mother of young children, who has professional, familial, and domestic obligations coming out of her ears, this standard can easily comes off as impractical, useless, even meaningless.

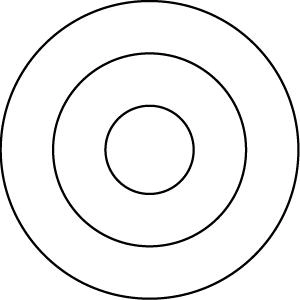

Imagine there are three concentric circles:

The smallest circle contains only your family and closest loved one. The next circle contains all your friends, acquaintances, colleagues, and neighbors, your community, your network. The final circle includes larger populations of strangers, such as your city or perhaps even your whole country. Which of these circles are we to focus on, if we wish to live according to the utilitarian standard? If we dedicate our energies toward creating happiness for one of the circles, we use up time and energy that cannot be spent spreading happiness to the other circles, so a choice must be made. But which is the most ethical option?

If I dedicate myself fully to building the best possible life for my children, wife, and parents (my smallest circle), I will certainly do a lot of good; but such a choice requires that I neglect, to a large extent, the wider world. An afternoon spent playing with my children is an afternoon not spent working at the local food bank; a weekend trip to Arizona with my father requires money that can not be donated to a more worthy cause. Do I truly meet the utilitarian standard if I pour most of my love, care, energy, wealth, and spare time into my family, but largely ignore the happiness of the wider world? Though the happiness within my home will be maximized, and my children more likely to grow up well-adjusted and emotionally stable (compared to children who are neglected), my dedication to the ‘greatest happiness principle’ is questionable at best.

If instead I dedicate my life to spreading well-being to the largest possible number of persons (the outer circles), I might accomplish truly great things!… but at a cost. Those who make such a choice – tireless activists for the poor, traveling community organizers, dedicated and focused union leaders, political dissidents – often make huge sacrifices in the personal sphere in order to fulfill the utilitarian ethic, an ethic which they believe requires them to serve the wider world. Yes my children will be sad if I don’t return at night to tuck them in because I’m working late at the homeless shelter, but so many others will benefit from my actions. If I’m away repeatedly, over the course of many years, my children may develop neuroses and abandonment issues and anger, may grow to hate me, may even have tragic lives. But over those years I could improve the lives of thousands of people. Is this the ethically correct sacrifice: spread joy to the greatest number, at the expense of a few (who happen to be my children)?

Mahatma Gandhi faced this very question, and he chose to serve the widest circle. He was a famously neglectful father, but a saint to a nation.6 Gandhi’s work for the poor, disenfranchised, impoverished, victimized, and low-caste was the ultimate display of utilitarian action.7 He dedicated his entire life to helping the less fortunate; this included extensive travel, the founding of communes, organization of large-scale protests, hunger strikes, the construction of a political party, travel to foreign nations to negotiate with world leaders, and many other activities which demanded his full concentration and energies. In the end his sacrifices and selfless actions improved the lives of millions of people around the world,8 and his legacy continues to inspire people today. However his children felt acutely the sadness and anger that come from having an absent father. His oldest son Harilal, whose relationship with Gandhi was always strained, never forgave his father for the ill-treatment, and later became an alcoholic. It seems there is no way to dedicate our full selves to the service of our closest loved ones AND to the wider world; there will always be a sacrifice one way or the other, and so we must choose.

On the surface the ‘greatest happiness principle’ appears to teach us that the price of a few very sad and neglected children is a reasonable price to pay, if their sadness purchases happiness for thousands of others. But this feels intuitively wrong. How can I be expected to ignore the unfathomably deep love bond I share with my two children? To put it more generally, how can I be expected to care more for strangers than I do for my loved ones? The utilitarian principle seems to insist that if my mission in life is to maximize happiness, it would be absurdly unethical to give special weight to the happiness of two children over the happiness of the larger population. Mill is very clear that one must be “as strictly impartial as a disinterested and benevolent spectator” when it comes to moral questions.9 A truly disinterested spectator would never choose the well-being of her own child over the well-being of many children. But I am tempted to reply (from the gut) that if it is unethical to dedicate my time and service almost exclusively to my children at the expense of thousands of others, then I am content to live an unethical life. Is this my own selfishness at work? Is it nothing more than a self-serving desire to relish the innate, mammalian love bond I feel for my offspring? No there is more to it than that. I genuinely struggle to see the merit in a moral system that tells me it is unethical to love my children (I say love because real love requires time and dedication). I’m ready to state boldly (and obviously) that of course it is ethical to love our children! So how do we reconcile this with the greatest happiness principle?

To begin to answer this question, let’s hit this from another angle: if we universalized the duty to serve the widest circle at the expense of the inner circle, would that actually create a happier world? Imagine if humanity widely practiced such a morality. Many millions of children would wind up neglected and traumatized by parents who felt obligated to serve the world instead of care for their children. Whole generations of young people would carry around the anger, bitterness, resentment, and sense of abandonment that ill-treated children often carry. If this tipped the scales away from general happiness and toward general sadness, if this ended up creating a worse world, we will have failed in our utilitarian mission, even if we intended our actions to create a happier world (this assumes we judge the merit of actions based on actual results as opposed to intended results, which is a debatable question in utilitarian ethics). It seems good for the species if we instead give extra weight to the happiness of our children, and bad for the species to create a generation of persons who have never been taught how to love or how to build lasting relationships. A world of neglected children is a sadder and angrier world. So how can this possibly be the utilitarian standard, if the enactment of such a principle would bring more pain than happiness?

Clearly the greatest happiness principle must mean something besides “always serve the greatest number“. Either that, or the principle itself is false according to its own utilitarian standard, since its enactment would make the world worse-off. It is deliciously ironic that the Greatest Happiness Principle would, if enacted, fail to maximize happiness. It also goes without saying that such a principle would also be completely impractical in the real world, since most parents feel morally and evolutionarily driven to help their offspring flourish. A utilitarian could make a compelling argument that we more fully satisfy the utilitarian standard (we create a happier world) by spending lots of time serving the smallest of circles: our tiny, helpless babies. As Utilitarianism.com says: “As there are obviously good utilitarian reasons to want the next generation of people to grow up to be emotionally healthy and capable agents, there are thus good utilitarian reasons to endorse the social norms of parental care that help to promote this goal.”10

That all being said, there must be some part of the utilitarian standard which does indeed require us to serve people outside our inner circle. We showed above that if we universalized the duty to serve exclusively the outer circle, it would, in the end, likely fail the utilitarian standard, since it would create a worse-off world. Well the same is true if we universalize the duty to serve exclusively our inner circle. Such a principle would require us to maximize happiness for our loved ones and acquaintances, while allowing (or encouraging) us to feel complete indifference or even hatred for strangers, foreigners, the poor, and members of political parties which oppose our own. If we have no moral obligations whatsoever to persons outside our narrow inner circle of acquaintances, we adopt for ourselves an isolationist moral philosophy: my duty of care extends to my own property line, and no further. This state of affairs, which weakens community bonds and encourages a myopic and lonely outlook toward the wider world, sounds tragically like the actual world in which we live.

Clearly utilitarianism, if it is to be useful in this big, scary world, requires a bit of nuance in its application. Mill strives to make utilitarianism a workable and useful theory for every day morality, so he sometimes downplays our individual commitment to the greater good, and tells us we are free to follow our hearts most of the time. This allows us a lot of leeway, but reduces the utilitarian standard to something vague and amorphous, an ethical principle that refuses to state clearly what it requires of us. Are we allowed to substitute the greatest happiness principle for the “create whatever local happiness you feel like creating” principle?

The reality is that real humans do love their children and wish to serve the wider world. Perhaps the answer then is simple: try for a balance. We should give as much love as possible to our inner circles, and occasionally (if we can spare the time) do some work for the outer circle. This seems like a practical solution, but as a moral theory it is weak tea: you’ve got a bunch of love to give, so spread it around in whatever direction feels right. There is some power in the aphorism, “as long as you are loving somebody, you are doing the right thing,” but is this really what utilitarianism is supposed to boil down to?

This idea that at times it is morally right to serve our families, while at other times it is morally right to serve the community, delivers us to the conclusion that utilitarianism cannot be the sole guiding moral law in our lives. Since we are expected to know when it is appropriate to switch between one or the other circle, there must be a principle that we can follow to guide us to the ethically correct decision, a principle which will tell us when to serve our families and when to serve others. Importantly, this principle cannot be utilitarianism itself, because serving any of the circles seems to meet the utilitarian standard in one way or another. A pluralism of ethical theories will be needed to navigate this unending dilemma.

So it seems utilitarianism (at least as Mill and Bentham understood it) cannot properly serve as an end-all, be-all moral system; more lenses are needed if we wish to fully see and appreciate all the complexities of real life. In the meantime, I will love my children, work hard at my job, show love to my wife, and generally work to maximize happiness within my smallest circle of loved ones. Perhaps I sacrifice the Greatest Happiness Principle in order to adopt for my family an “Ethic of Care,” and maybe this is right, even if it means failing to maximize the happiness of the community (failing even to come close to that goal). The necessity, the urgency, the implacability of the love I feel for my children is something utilitarianism simply can’t resolve, unless it abandons (or severely limits) the Greatest Happiness Principle. If it refuses to abandon the principle, it is revealed to be fraudulent as an ethical theory. If it does abandon the principle, what is left of the moral theory besides: “do as much good as you feel like?”

Related article:

Is J.S. Mill’s utilitarianism really “ethics” at all?

Notes

- Whenever I quote from Mill’s Utilitarianism (1863), I will cite the chapter/paragraph in the following format: Mill, Utilitarianism, II/2: “The creed which accepts as the foundation of morals, Utility, or the Greatest Happiness Principle, holds that actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness. By happiness is intended pleasure, and the absence of pain; by unhappiness, pain, and the privation of pleasure. To give a clear view of the moral standard set up by the theory, much more requires to be said; in particular, what things it includes in the ideas of pain and pleasure; and to what extent this is left an open question. But these supplementary explanations do not affect the theory of life on which this theory of morality is grounded- namely, that pleasure, and freedom from pain, are the only things desirable as ends; and that all desirable things (which are as numerous in the utilitarian as in any other scheme) are desirable either for the pleasure inherent in themselves, or as means to the promotion of pleasure and the prevention of pain.” ↩︎

- In Mill, Utilitarianism, IV/8, the intrinsic goodness of happiness is a key feature of Mill’s famous ‘proof’ that utilitarianism is right: “…there is in reality nothing desired except happiness. Whatever is desired otherwise than as a means to some end beyond itself, and ultimately to happiness, is desired as itself a part of happiness, and is not desired for itself until it has become so. Those who desire virtue for its own sake, desire it either because the consciousness of it is a pleasure, or because the consciousness of being without it is a pain, or for both reasons united; as in truth the pleasure and pain seldom exist separately, but almost always together, the same person feeling pleasure in the degree of virtue attained, and pain in not having attained more. If one of these gave him no pleasure, and the other no pain, he would not love or desire virtue, or would desire it only for the other benefits which it might produce to himself or to persons whom he cared for. We have now, then, an answer to the question, of what sort of proof the principle of utility is susceptible. If the opinion which I have now stated is psychologically true- if human nature is so constituted as to desire nothing which is not either a part of happiness or a means of happiness, we can have no other proof, and we require no other, that these are the only things desirable. If so, happiness is the sole end of human action, and the promotion of it the test by which to judge of all human conduct; from whence it necessarily follows that it must be the criterion of morality, since a part is included in the whole.” ↩︎

- Russ Shafer-Landau, The Fundamentals of Ethics, 4th ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2018), 120. ↩︎

- Jeremy Bentham, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (New York: Hafner Press, [1789] 1948), 1. ↩︎

- Mill, Utilitarianism, II/11 ↩︎

- See Ramachandra Guha’s Gandhi Before India (New York: Vintage Books, 2013) for a heart-breaking look at Gandhi the absentee (yet often still over-bearing) father. ↩︎

- Gandhi was actually quite critical of utilitarianism the political philosophy. He saw the ‘greatest happiness principle’ as justification for majority rule and the exploitation of minorities (happiness and economic prosperity are generated for the majority, at the cost of poverty, disenfranchisement, and unceasing labor for the minority). Instead of the greatest happiness of the great number, Gandhi preferred the greatest happiness of all, a concept which he called Sarvodaya, a Sanskrit term meaning “Advancement of All”. Despite this critique of political utilitarianism, Gandhi’s personal actions typified the utilitarian ethic, which requires immense personal sacrifice as a means to generate as much happiness for others as possible. For an example of Gandhi’s critique of utilitarianism, see his article in Indian Opinion dated May 16, 1908, which appears in The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (New Delhi: Publications Division Government of India, 1999), Vol. 8, 316-319. ↩︎

- This is a debatable point. However the debatability of this point might not have bothered Gandhi. The philosophical text which most excited Gandhi was Bhagavad Gita which instructs us to focus more on intentions than outcomes. Like utilitarians, we should aim to do as much good as possible in the world, but we should not allow ourselves to become emotionally invested in outcomes outside our control. God may not allow our plans to come to fruition, and we may even be forced to endure tragedy and heart-break and loss; but we must continue to strive for a better world no matter how many times we fail. This is the key to living an ethical life and flourishing personally. This message was very important to Gandhi, who encountered many failures and set-backs and unintended consequences during his long career. For example, despite Gandhi’s best intentions, his actions as an anti-colonial activist were an indirect cause of the horrible sectarian violence that erupted after the partitioning of India in 1947. So though Gandhi made tremendous sacrifices to improve the lives of his people, the actual short-term outcome for much of the Indian people was a mixed bag. There is a lesson here for utilitarians: though a person may sacrifice much in order to maximize happiness for the many, there is no guarantee that she will be successful at maximizing happiness. If we judge a person’s actions solely according to the actual outcomes they produce, we are forced to condemn a person who sacrifices everything in order to spread happiness to the masses but ultimately fails to increase the general happiness. This would mean that Gandhi was not acting ethically any time that his actions inadvertently led to more pain than happiness (any time he failed to maximize utility). But this feels intuitively incorrect, given the sacrifices Gandhi made in the service of so many persons, and given the limited knowledge all humans have about how our decisions will affect the future. The Gita teaches that if you have an honest intention to do good in the world, you work selflessly toward your goal, and you fail, you are still living ethically. Later utilitarian thinkers have distinguished between the actual utility of a certain action (the actual outcome), versus the expected utility of that action (the outcome we expect), which allows utilitarianism to shrug off some of its consequentialist tendencies: if we judge actions based on their expected utility rather than actual utility, we really shift from focusing on outcomes and instead focus on intentions. This brand of utilitarianism teaches: “as long as we truly intend our actions to maximize the happiness of others, our actions are ethical even if we ultimately fail in our goal”. Gandhi would not have called this concept ‘utilitarianism’, but would have instead called it the message of The Gita. Regardless of what he called it, this ethic formed the foundation of Gandhi’s philosophy of action. See: Uma Majmudar’s “Mahatma Gandhi and the Bhagavad Gita” on The American Vendantist website, published Dec. 6, 2014. If you want to explore the philosophy of The Gita further, read this essay. ↩︎

- Mill, Utilitarianism, II/21. ↩︎

- R.Y. Chappell and D. Meissner, “The Special Obligations Objection,” in R.Y. Chappell, D. Meissner, and W. MacAskill, eds., Introduction to Utilitarianism, <https://www.utilitarianism.net/objections-to-utilitarianism/special-obligations>. ↩︎