So I’ve decided to become an expert on Marxism.

Why? Well that’s a good question. Let me come back to that.

My ultimate goal is this: I want to do something about climate change. How can becoming an expert on Marxism help fight the climate battle? I’m not exactly sure, but that’s what I hope to find out.

First let me talk for a moment about climate change. It isn’t like the other political issues of our time. Sure when most media figures talk about gun control, abortion, voting rights, minimum wage laws, free trade, etc., they act as if the world itself hangs in the balance. But climate change stands above all those other issues. It is a real-life bona fide existential threat to humankind. When I picture in my mind the tribulation my children and grandchildren will face because of climate change, and the ambivalent responses our so-called leaders tend to offer toward addressing the crisis, I’m left feeling empty inside. The sense of frustration, impotence, and hopelessness are intense, I can hardly bear to engage with the issue whatsoever. Climate change is the reason I gave up watching cable news a few years ago; I simply can’t stomach to watch politicians and media outlets obsess about small-ball issues while ignoring or down-playing the actual looming threat that is staring us directly in our faces.

There are many reasons why politicians and corporate media outlets choose to ignore or downplay climate change, or pretend it isn’t caused by human activity, or cast doubts upon climate science itself as a field of study, but I will not go into that here. The point is that I want to do something about climate change. I want to contribute any way I can.

But how?

It just isn’t possible for me to change jobs and start working at a climate-focused non-profit, at least not right now. We have two young children who need our love, time, attention – and our financial stability. Our son Charlie has leukemia, so we need a good healthcare plan and a steady enough income to pay hospital bills. The point is that I can’t simply leave my job and go work for some organization that studies carbon capture technology. I have people who depend on me, so my life must maintain a certain level of stability for their sake. I won’t be switching careers just yet.

I’m also not a scientist. I do not have the necessary knowledge or credentials to work as a climate researcher. I would love to help advance the crucial research efforts that are taking place on the frontier of climate science, but that kind of research is not my strong suit. So I won’t be joining the army of citizen scientists who are seeking some kind of scientific solution to this problem.

And If I am being completely honest, I’m probably also not cut out to play an active role in a climate-focused political party either. Maybe it’s because I just don’t do particularly well with committee politics. Put me in a situation where I’m a member of a committee and we need to discuss and decide on an important issue, and I completely lose my mojo. Maybe I’m a bit too outspoken and tactless when debates gets started, which is not a helpful trait if one is trying to build up a fledgling political party (or trying to talk politics with friends). Or it could be that I have problems with authority; this has been suggested at various times in my life. So I’m not sure entering into party politics is the right path for me. I would still like to join a climate-focused party, but I’d prefer a behind-the-scenes role.

So what the heck can I do to help? How can a guy with no science background or political acumen, possessing very little free time or spending money, contribute to the most critical scientific and political problem facing mankind? I had to turn this problem over in my mind for a long while. What I came up with is this: I can write.

Maybe by writing I can be of some use. But what will I write about? Well I’m not sure about that yet either. I’ve never been especially serious about writing, though I’ve always known I have a certain knack for it. Thus far I’ve mostly only written about music composition. But I feel an intense urge to write something, anything, that might help with this cause. The motivation is there, so maybe that’s how I can play my small part, how I can help move the ball down the field.

Ultimately what I want to write about is not science but philosophy, political philosophy to be exact. Political philosophers study how people solve big problems, and sometimes they develop potential (or even groundbreaking) solutions to those problems. Climate change is the biggest problem we (our species) may ever face, so studying how our species can best respond to the crisis seems a fitting use of my time. Perhaps through philosophy I can help develop some workable solutions, collaborate with others on larger projects, find a suitable role for myself in a climate-focused party, and make some kind of impact. It’s a long shot I know, but it’s better than where I’ve been up to now: frustrated to such an extent at my inability to help in any way, that extreme apathy is my only weapon against despair.

I’ve chosen Marxism as my starting point. Marxism is a philosophical tradition that focuses on critiquing systems that are unjust, exploitative, and oppressive. It rips the mask off and reveals all the layers of rot lying beneath the surface, all the contradictions and lies. It also proposes (sometimes revolutionary) solutions to these problems; it is not a tradition that supports empty theorizing, but instead it seeks to pair theory with actual practice. In other words, Marxism takes a stab at understanding and solving big problems. So I will start there, and see what it has to offer. I’m not sure whether the solutions Marxism proposes will be worth a damn in the climate fight, but as I said it’s a starting place.

I am no expert in Marxism, so I will have to start from scratch. This is going to mean an intense course of study, and hopefully a lot of writing as I process these new ideas (new to me anyways). I genuinely wish to discover what concepts/philosophies/worldviews/lenses exist in the Marxist tradition, and whether any of them can actually be put to good use solving the climate crisis in the real world. And while there is a relatively new thread of Marxist thought that specifically examines the intersection of Marxism and environmentalism (see as an example: Organic Marxism – An Alternative to Capitalism and Ecological Catastrophe by Philip Clayton and Justin Heinzekehr), I will not start my course of study with environmental Marxism. I will start instead with Karl Marx’s own writings, and from there I will branch out into the writings of his predecessors and peers, and then onto the many diverse writers who took Marx’s worldview and extended it in so many directions. Along the way I will also read critiques of Marx and Marxism, as well as writers from other philosophical traditions who shared their views on Marxism, and whatever other angles I haven’t thought of yet. I’m looking to dive deep into this tradition, and see if I come out a changed man on the other side.

I am not starting this endeavor as a Marxist. Though my political leanings have always been on the left, I do not at this time call myself a Marxist, nor do I exactly understand what that even means. Can one be a Marxist if he simply concurs with Marx’s critique of capitalism? Or does one also have to believe in Marx’s vision of a future communist utopia to call oneself Marxist? For that matter, what did Marx really say about the future? Did he really advocate for a “dictatorship of the proletariat,” or was that just something Lenin added in? Did Marx actually believe that we could usher in communism via a worldwide revolution, or was that more of a metaphor for long-term change? How much of Marxism is just pure critique of the status quo, and how much consists of potential solutions to our problems? I want to know what this tradition has to offer a sick, sad world on the brink of ecological collapse. If there is anything useful in there, I want to learn it.

I also plan to separate out the parts of the tradition that are beyond saving: hopelessly outdated analyses, advocacy of programs for which the destructive or dangerous results far out-weigh potential benefits, one-sided or fallacious or propagandistic philosophical reasoning, and critique of a long-past world whose relevance to our own has faded beyond usefulness. One could say I am hunting for a “workable” Marxism, a “realistic” Marxism, one with real applicability in the modern world, shed of its darker or utopian elements. I seek in Marxism a tool that can be harnessed to bring beneficial change. I’m not sure at this time how much of this mission is possible. Critics tell me that it isn’t at all possible. It seems that most conservative (and many liberal) pundits want me to believe that 1) Marxism is evil and dangerous, 2) it will necessarily lead to the destruction of freedom, democracy, our children, religion, America, everything we hold dear, etc., and 3) it is also hopelessly irrelevant, a product of the 19th century that belongs in the dustbin of history. But listening to those guys – those corporate pundits whose large paychecks depend on their ability to endlessly and relentlessly flog Marxism – I get the impression they are really saying “whatever you do, don’t look over there! Don’t question capitalism. The status quo is perfect. Don’t look behind the curtain!” Well I intend to take a peek.

I recognize that Marxism has a checkered past. This philosophical/economic system has been blamed for many epic historical catastrophes, including genocides and totalitarianisms. I intend to discover exactly how the writings of Karl Marx are linked across the generations to Stalinism. I am going to learn in what ways those views were distorted or adapted by myriad thinkers and politicians and polemicists along the way. I want to examine the good and the bad of this tradition, with the intention of cutting out the bad parts and salvaging only what is useful. Are there parts of the Marxist philosophical framework that differ wildly from the dystopian Stalinist nightmare many Americans picture when they think about Marxism, or is totalitarianism the inevitable result of Marxism? Can we have Marxism without secret police, without gulags, without severe limitations on personal freedoms? For that matter, can we have Marxism without revolution, without violence? Based on what I’ve read so far, Marxist scholars have many disagreements on these questions.

Though many Americans likely picture Stalin as the timeless symbol of Marxism, in reality Stalinism is but one thin branch of the enormous Marxist tree. At this early stage in my studies I can already conclude that there is no longer just “one Marxism,” but many. During the past 150 years, a wide range of Marxist scholars and authors have weighed in on this tradition, each adding his or her own unique spin, each adapting or modernizing the tradition to meet the realities of the author’s time, each taking it in a new and exciting direction. In fact Marxism has become like a huge cave with countless labyrinthine tunnels; I plan to explore these tunnels and see where they lead (or where they dead-end). Of course not only Marxists have weighed in on Marxism; moral philosophers, feminists, economists, political scientists, and legal scholars have all explored how Marxism can weave and intertwine with these various disciplines. On top of that, a handful of countries have attempted to implement Marxist programs, and each time the result has been that Marxism combines with the culture of that country and comes away changed (and also Marxism changes the culture of the country as well). To make the tradition even more complex, modern Marxist organizations and parties are each contributing their own novel ingredients to the stew.

Despite all this vibrancy and diversity of thought, Marxism has been declared a dead tradition countless times (especially after the fall of the Soviet Union). Yet the tradition continues to attract talented writers and intellectuals to this day. I suspect there is something of monumental value here, and I intend to seek it out – and to disregard all that is toxic. So I’m aiming for that workable form of Marxism. And if that turns out not to exist (or if it only exists in such a corrupted form that it decays quickly or does more harm than good), then at least I’ll know that. But I’m hoping it exists! Above all, I hope that the collected wisdom of the Marxist tradition can actually help us fix our big problems.

This is only my first step toward becoming a political philosopher; Marxism is just my starting place. I’m uncertain where this study will lead me, but I intend to go as deep into it as I can. I intend to take it seriously. And of course I will always keep in mind my over-arching long-term goal: to work on climate change. But I still need to start somewhere. This starting point will allow me to work on my research/writing chops, build up a kind of foundational knowledge that will make it easier to jump into other areas of study later, and perhaps even uncover unforeseen truths that will help me build a philosophical system of my very own someday.

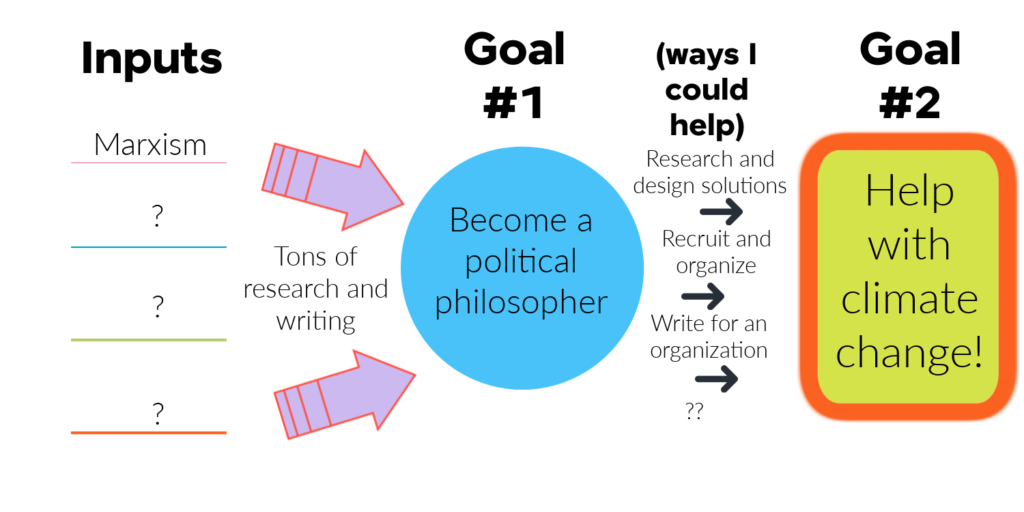

This graphic lays out the steps of my very rough “how I will help fight climate change” plan:

Obviously there are a lot of gaps in there. I’ll work on filling those in as I go. You may also notice that “enroll in a university” is not currently listed on there. Let me just say that I would love to pursue a higher degree in political philosophy. If I get the opportunity to do so, I will jump at it. However at this moment in my life that just isn’t feasible. I have neither the time nor the money to become an academic – though becoming an academic is my secret dream. Maybe when my kids are older I will make the jump, a step which is probably crucial if I actually wish to accomplish my goals. Not only would I learn so much from having peers and teachers (rather than studying alone), but the academic life would also give me the opportunity to build networks of friends and colleagues, professors and mentors, publishers and journals contributors. If I ever wish to see my work published outside of this website, those connections will be critical. Not to mention that the academic life gives one the opportunity to shine, if one sees fit to take up the challenge. There are endless research opportunities, access to the best libraries in the world, and colleagues with whom to collaborate on writing projects and new ideas; in other words universities offer a support network for those who wish to take their studies seriously, and a platform for those who want to break new ground. I believe I could rise to that occasion if given the opportunity, but that is for another day.

You may also wish to know why I don’t simply skip all the rigamarole and get straight to helping. Why not simply start writing about climate change right now, instead of going through all those extra steps? Why wait!

My answer is: I don’t want to just write about climate change. I don’t want to be a pundit, simply commenting on the here and now (as if I could even do that properly without research). I want to develop solutions! But I don’t feel ready to do that yet; I don’t feel like I know enough. I don’t know what’s possible or what’s been tried. I don’t have foundational knowledge on my topic – not the science of climate change, nor the political philosophies that might address it. If I hastily crank out a bunch of essays right now without doing any research, they will be full of factual or logical errors. They would certainly demonstrate my ignorance and lack of erudition on my topic, but probably would not accomplish much more than that. No, I need to do some studying first. I need to learn how to think and write and argue like a philosopher.

So onto Marx then!

Selected Writings by Marx and Engels

- “On the Jewish Question” by Karl Marx

- Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts of 1844 by Karl Marx

- The German Ideology by Karl Max and Friedrich Engels

- Capital (3 vols.) by Karl Marx

- Manifesto of the Communist Party by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

- The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte by Karl Marx

- Critique of the Gotha Program by Karl Marx

- Socialism: Utopian and Scientific by Friedrich Engels

- Anti-Dühring by Friedrich Engels

- Revolution and Counter Revolution by Friedrich Engels

Some areas I plan to explore:

- Marx’s general contributions to philosophical/political thought

- Marxism and Rights/Liberty

- Marxism and Materialism

- Marxism and Humanism

- Marxism’s views on parliamentarism (using the state apparatus to create change)

- Marxism’s different views on revolution

- Marxism and Moral Philosophy

- Marxism and Religion

- Marxism and Political Violence

- Marxism vs. Anarchism

- Marxism and Science (Marxism is sometimes called a science)

- Marxism and Grand Prophesies about the Future

- Marxism and Human Nature

- Marxism and Democracy

- Marxism and the Dialectic

- Criticism of Marxism

- Distortions of Marx’s Ideas (i.e. how the ideas changed over time)

- Marxism and its application in various countries

- Marxism today (current Marxist movements/groups/parties and the arguments/tactics they employ)

- Marxism and Environmentalism

I’m not particularly interested in writing an exhaustive study of how Karl Marx discussed certain themes or issues. I’m not after finding the ultimate orthodox Marxism. Instead I want to study the tradition, which outlived Marx and changed in countless ways as later scholars and thinkers expanded the tradition. The tradition lives on to this day, and changes every time a new writer picks it up. This allows the tradition to change with the times, and adapt to humankind’s changing needs. It’s a living tradition.

Here are some of the different thinkers and schools of thought I plan to study:

- Predecessors: Epicurus, Democritus, Aristotle, Lucretius, Fourier, Proudhon, Robert Owen, Spinoza, Hegel

- Classical Marxists: Marx, Engels, Karl Kautsky, Rosa Luxembourg

- Social democrats and reformists: Bebel, Liebknecht, Eduard Bernstein, Lasalle

- Leninists and Trotskyists: Lenin, Trotsky (perhaps also Alex Callinicos, Perry Anderson, Hal Draper – not sure if these guys would actually call themselves Leninists).

- Western Marxists: Lukacs, Antonio Gramsci, Karl Korsch, Ernst Bloch. Sometimes included: Bertolt Brecht, Wilhelm Reich, Erich Fromm, Alfred Sohn-Rethel

- Frankfurt School: Horkheimer, Marcuse, Habermas, Adorno, Leo Lowenthal, Walter Benjamin, Alfred Schmidt

- French Hegelians: Henri Lefebvre, Lucien Goldmann

- Existentialist Marxists: Sartre, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Simone de Beauvoir

- Anti humanist, anti-Hegelian Marxists: Althusser, Galvano Della Volpe

- Autonomist Marxists: Tony Negri, Harry Cleaver, Michael Hardt, John Holloway

- Analytical Marxists (anti-dialectic): GA Cohen, Jon Elster, Adam Przeworski, John Roemer, Robert Brenner

- English Marxists: Maurice Dobb, Christopher Caudwell, Maurice Cornforth, Raymond Williams

- Neo-Marxists (Post-Marxists): Samuel Bowles, Herbert Gintis

- Marxist historians: Christopher Hill, Eric Hobsbawm

- Marxist writers working today: Philip Clayton, Justin Heinzekehr, Zizek, and many many more.

- Critics of Marx: Leszek Kolakowski, Thomas Sowell, Friedrich Hayek, Ludwig Von Mises, and many many more.

This endeavor may not actually lead anywhere useful, but it feels good to try something. It feels right to learn and better myself and expand my mind, even if climate change still kills us all in the end. But who knows, maybe I’ll learn something that makes a difference to someone somewhere. All I can do is try.