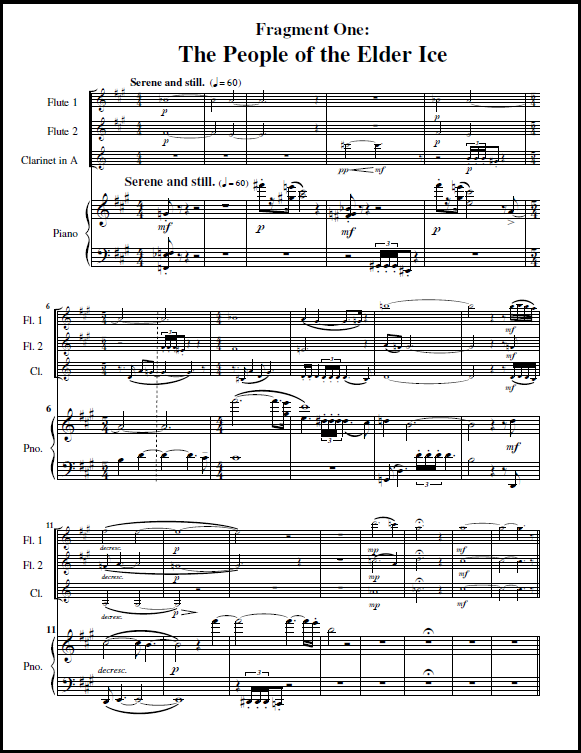

Quiquern is a five movement piece of music for piano, two flutes, and a clarinet, based on a short story by Rudyard Kipling.

Here is the story behind the music .Quiquern: The Magic Songs and Hunter’s Return

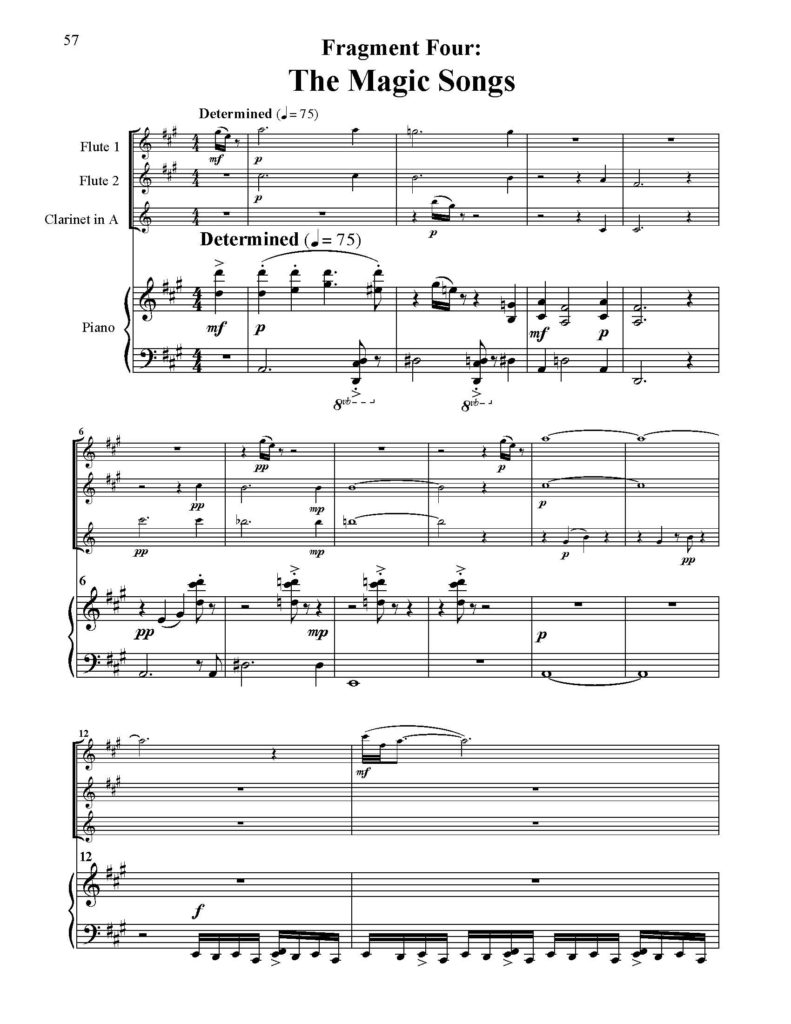

This next fragment of Quiquern is called “The Magic Songs”. Famished and delirious, Young Kotuko and the girl set out alone into the blizzard to find food for the starving village. As the dark and the cold and hunger devour them, the two children rave and hallucinate, unhinging themselves from the realm of men and into the realm of gods. As they descend, they sing songs of magic, songs buried deep in their memories, in their blood. Their voices rise and fall with the frozen wind.

And through this silence and through this waste, where the sudden lights flapped and went out again, the sleigh and the two that pulled it crawled like things in a nightmare — a nightmare of the end of the world at the end of the world.

The girl was always very silent, but Kotuko muttered to himself and broke out into songs he had learned in the Singing–House — summer songs, and reindeer and salmon songs — all horribly out of place at that season. He would declare that he heard the tornaq growling to him, and would run wildly up a hummock, tossing his arms and speaking in loud, threatening tones. To tell the truth, Kotuko was very nearly crazy for the time being; but the girl was sure that he was being guided by his guardian spirit, and that everything would come right. She was not surprised, therefore, when at the end of the fourth march Kotuko, whose eyes were burning like fire-balls in his head, told her that his tornaq was following them across the snow in the shape of a two-headed dog. The girl looked where Kotuko pointed, and something seemed to slip into a ravine. It was certainly not human, but everybody knew that the tornait preferred to appear in the shape of bear and seal, and such like.

It might have been the Ten-legged White Spirit–Bear himself, or it might have been anything, for Kotuko and the girl were so starved that their eyes were untrustworthy. They had trapped nothing, and seen no trace of game since they had left the village; their food would not hold out for another week, and there was a gale coming. A Polar storm can blow for ten days without a break, and all that while it is certain death to be abroad. Kotuko laid up a snow-house large enough to take in the hand-sleigh (never be separated from your meat), and while he was shaping the last irregular block of ice that makes the key-stone of the roof, he saw a Thing looking at him from a little cliff of ice half a mile away. The air was hazy, and the Thing seemed to be forty feet long and ten feet high, with twenty feet of tail and a shape that quivered all along the outlines. The girl saw it too, but instead of crying aloud with terror, said quietly, “That is Quiquern. What comes after?”

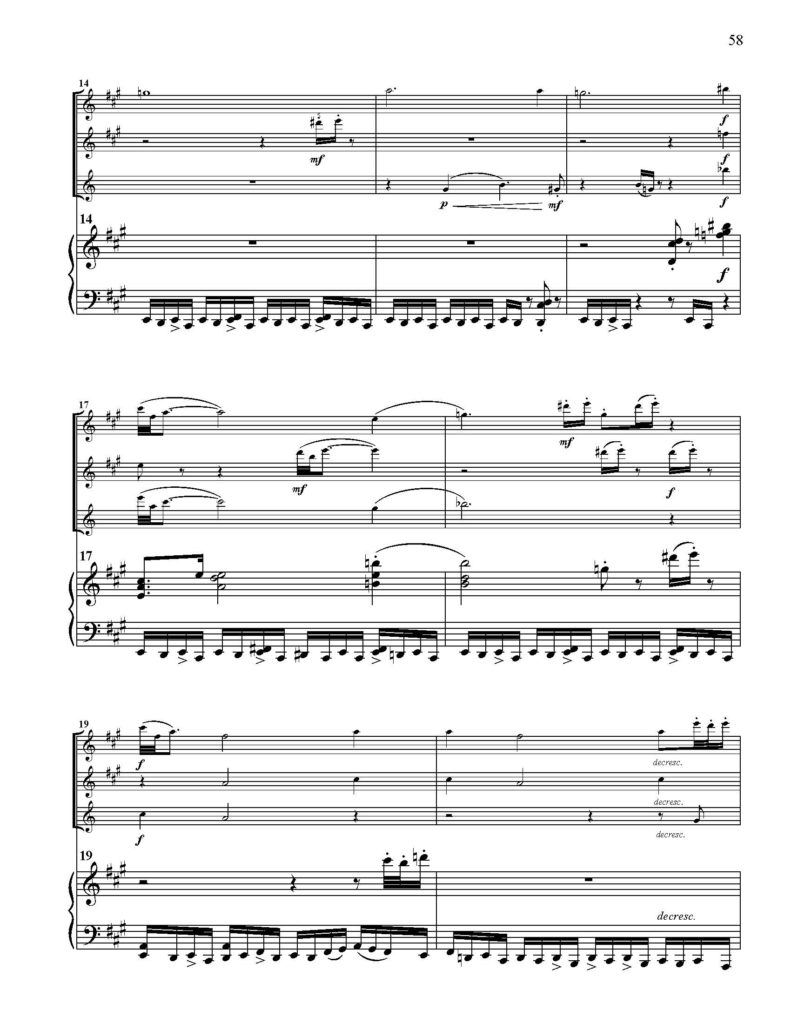

This is the final music of Quiquern. At the end of the story, the dogs lead the boy and girl to a crack in the ice where seals are coming up for air. They kill as many seals as they can carry, and hurry them back to the village. The people rejoice as famine is averted just in time. They sing and light candles made of seal fat.

Kotuko and the girl took hold of hands and smiled,

for the clear, full roar of the surge among the ice

reminded them of salmon and reindeer time

and the smell of blossoming ground-willows.

Even as they looked, the sea began to skim over

between the floating cakes of ice,

so intense was the cold;

but on the horizon there was a vast red glare,

and that was the light of the sunken sun.

It was more like hearing him yawn

in his sleep than seeing him rise,

and the glare lasted for only a few minutes,

but it marked the turn of the year.

Nothing, they felt, could alter that.

This ending seems to think of itself as a happy ending. But that’s not really what it is. It’s not a sad ending either. The village is well-fed for today, and their way of life continues the way it has for a thousand years. There is something truly magical about that. But what happened this winter will happen again. The village’s survival is always balanced precariously upon a precipice. As the camera pans out, we are reminded that all around the happy village is an endless frozen desert, cruel and dark, and so very cold. A single warm ember in a vast field of ice.

Perhaps that is a metaphor for all of humanity. Everything that we do and everything we care about and everything we’ve ever created and everything we remember and cherish is but a tiny ember in the blackness of space. How hard we all try to keep it lit; how vast and cold and uncaring is the universe.

Does that mean we shouldn’t live our lives to the fullest? Of course not! It’s even more reason to appreciate life. The feel of a baby’s skin on one’s cheek, the laughter of a life-long friend, the warm embrace of a lover, the taste of well-prepared food, the memories of good times, the hopes and dreams and aspirations we all nurture in our hearts; these things keep us warm and snug through the winters of life, even if deep down we know that the dark need not attack us directly to see us finally defeated, it need only wait.

A Letter to My Father

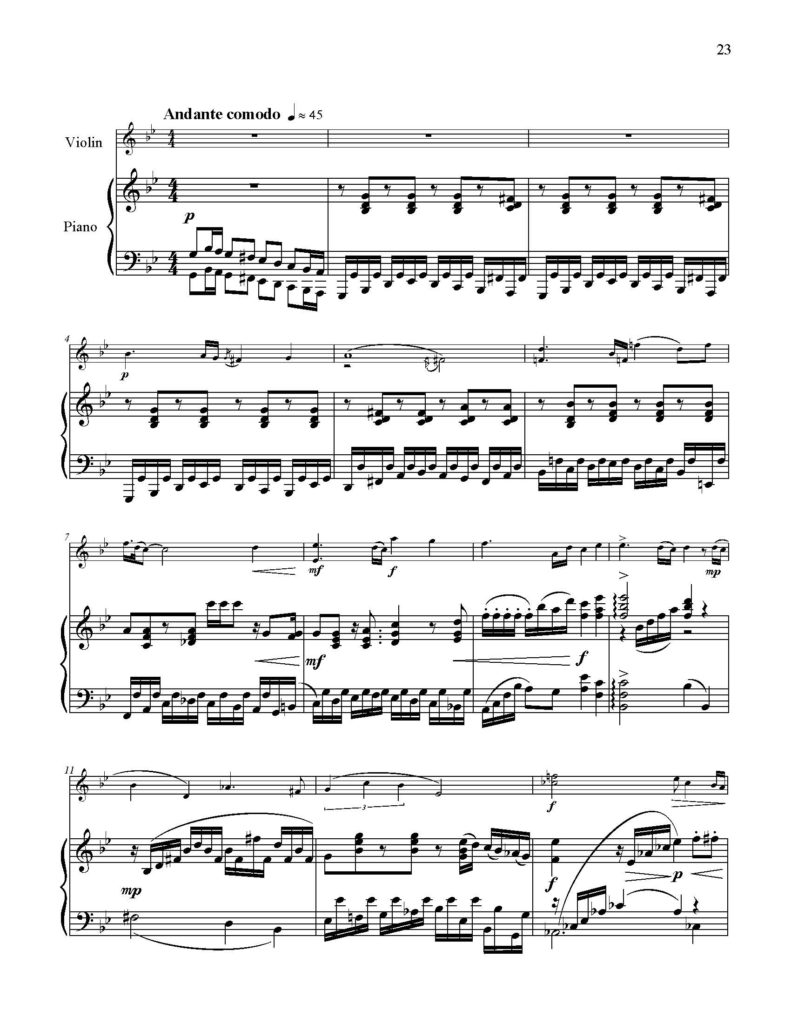

This evening I added the finishing touches to a piece I composed back in 2008, “A Letter to My Father.”

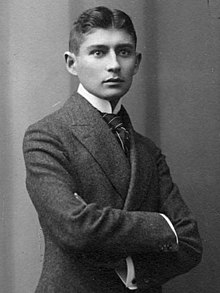

This piece is actually the third movement from my string quartet “Jackdaw.” Therefore at its heart it is based on the life and writings of Franz Kafka, like all the other music in that quartet. However this music has special meaning for me as well (also like all the music in that quartet). It feels especially meaningful during this current time in my life, when my own interactions with my father have become so very strange.

Kafka’s Letter to his Dad

When Kafka was about 36, he wrote a nasty letter to his dad. Apparently his father Hermann was a pretty difficult guy, constantly ridiculing Kafka for being a weakling, while refusing to care one bit that his son was a genius. Kafka’s stories are real mind-benders. The realities they portray are just “off” enough that they feel like they could be real life. One can recognize the landscape, envision oneself living in that world, but something in the reality is very wrong. Sometimes it’s hard to put one’s finger on… but impossible to ignore. Like the work of H.P. Lovecraft, the stories have the power to make one doubt one’s own world, to make one doubt mankind as a whole. It’s delicious writing, and frankly still horrifying to this day. Despite young Franz’s clear talent, Poppa Kafka just didn’t respect his son, and he made that known at every opportunity.

By age 36, Franz was tired of Hermann’s crap. He busted out some paper and really let Dad have it, for 45 hand-written pages. In his own way, Kafka believed that this letter would help heal their relationship, but in reality the letter was full of complaints, accusations, and invective. He plumbed the depths of his own hurt, and wrung the emotions out onto the page. If the letter is to be believed, Hermann was a toxic and narcissistic hypocrite, an abusive tyrant who never gave his fragile son even a kindly word or friendly look in all his life. The writing is heart-breaking and so very relatable, ripe as it is with a certain timeless pain that has been felt by so many sons across so many generations.

In one episode, Kafka describes a traumatizing experience from his childhood: one evening at bedtime he was begging his father for some water (perhaps even being a bit bratty about it), when his father, always a large and intimidating man, burst into his bedroom without warning and, in a rage, grabbed the small boy and locked him outside on the balcony with nothing on but his thin cotton sleep shirt. Kafka writes:

I was quite obedient afterwards at that period, but it did me inner harm. What was for me a matter of course, that senseless asking for water, and the extraordinary terror of being carried outside were two things that I, my nature being what it was, could never properly connect with each other. Even years afterwards I suffered from the tormenting fancy that the huge man, my father, the ultimate authority, would come almost for no reason at all and take me out of bed in the night and carry me out onto the balcony, and that meant I was a mere nothing for him.

Franz Kafka, from Letter to His Father

Not only is this a sad story of parental mismanagement and emotional scarring, but it is also such a great insight into why so much of Kafka’s writing features nameless, faceless authority figures who carry out irrational sentences with a total lack of empathy or emotional connection. Moments that feature characters like that are some of the more disturbing vignettes from his stories; they make it all too easy to picture oneself being dragged away by faceless agents of the state who have no sense of human morality or concern for life. Kafka was able to translate his tragic daddy issues into terrifying metaphors for what it’s like to live in modern society. Now THAT’S how to cope with a bad upbringing.

Let’s all write letters to our dads!

Funny story: I had to send a letter to my own father recently. Mine was not as nasty as Kafka’s, nor was my father anywhere near as abusive as Hermann. But father-son relationships can be all varieties of strange, and mine definitely falls on that spectrum. I won’t go into the details here, but suffice it to say that at pretty much the same age as Kafka when he wrote his letter, I felt compelled to write a letter to my dad that I wish I didn’t have to write. It delivered the message, though I’m not sure it did anything to heal our relationship.

When Kafka completed his letter, he hand delivered it to his mother, and asked her to bear the letter to his father. Her mother read it once and immediately decided to hide it forever. As much as Kafka might have hoped his manifesto would help heal old wounds, his mother felt differently, and refused to take any part in provoking the monumental explosion that would likely follow should Hermann ever read it. My own letter was delivered directly to my father, though I’m actually not sure he read it. One can never know these things when direct communication becomes impossible.

Long story short, this music ain’t just about Kafka. I hope someday someone writes about how I skillfully took my familial pain and transformed it into timeless art we can all relate to. Whether or not that ever happens, I will say this: writing the music always makes me feel better.

The Painted Bird

When I read The Painted Bird by Jerzy Kosiński, it disturbed me, in that special way that only great literature can. It tore my brain up, left me feeling very uncertain about who I was, about my own species. This music just had to come out.

Music that reminds me of dog sitting

I wrote this on a ranch. I wrote this at the radio station, late late at night. It’s a song of love. It’s a song about feeling alone.

On the day I finished it, I also finished On Chisel Beach by Ian McEwan. This music wrapped itself around that story, and both were planted deep into my brain. Both the music and that story complain and ache and worry, they both drag it out when it doesn’t need to be that complicated. Both improve with age, with patience, with repetition.

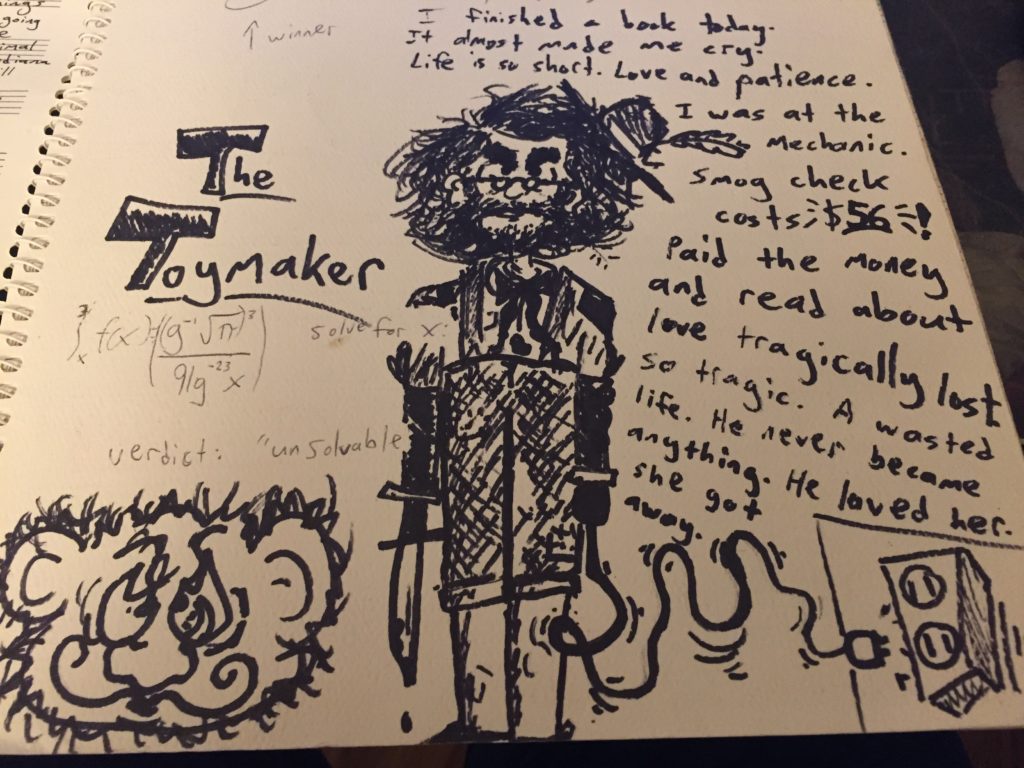

On the day I finished it, I drew this picture:

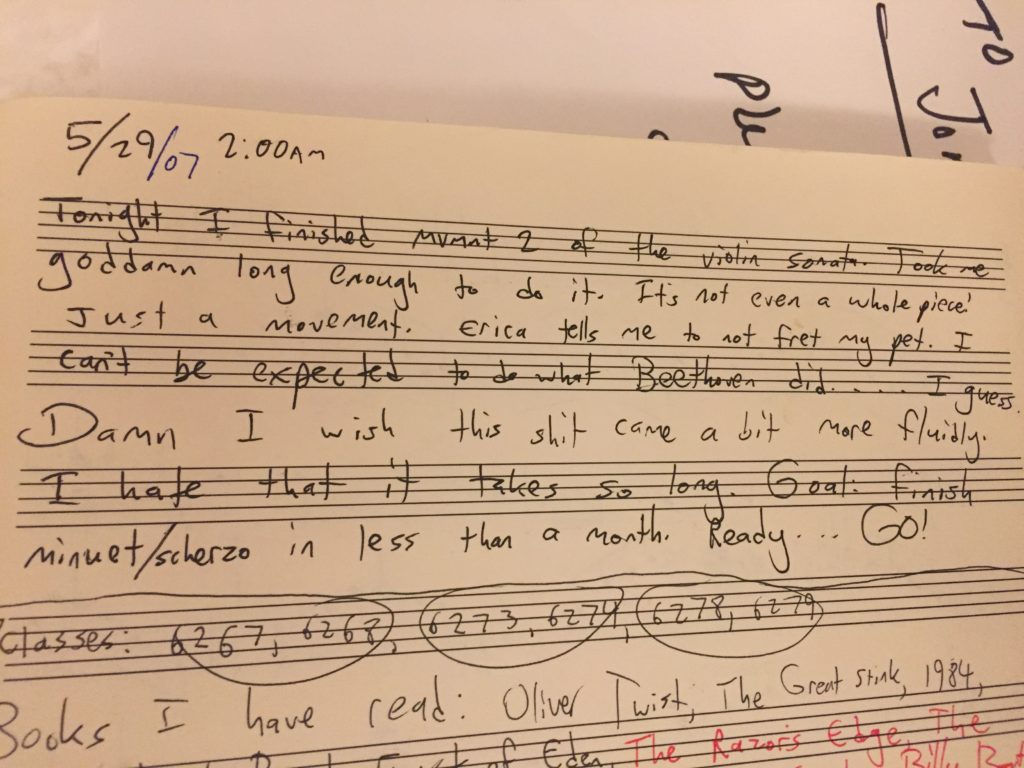

I also fretted about composing too slowly:

Writing words on sheet music is easier than writing music. Maybe I just need to write music as often as I write words.

This song reminds me of sitting up until all hours of the night, on a couch that wasn’t my own, in a strange house, watching WWII documentaries and checking to see if we’d accidentally let the coyote eat the cat.

It reminds me of the last grasping days of college. I was spending most of my time grasping, grasping at what?… grasping at something.

It reminds me of emerging from a dark cavern to greet the morning sun. It reminds me of waiting, waiting, waiting to grow up.

Years and years and years after I finished the music, I played it for someone. She said, “You’re really starting to get good at this.” I pretended that the music was truly new.

Who Am I Stealing From Today? (David Wise)

In early January, full of fresh energy and creative juice, I saw the music in a different light and dove headfirst into some new material. In two days I created an entirely original fragment: The Singing House.

Fragment 3: Quaggi – The Singing House

Come on a musical journey with me.

On the far side of the village is the Quaggi – The Singing House. Only men may enter; it is where they go to pray. In times of plenty, the men sing hearty songs of gratitude to the various gods of the Arctic. In times of desperation, they fall into a trance of smoke and dark and sweat and hunger. Arms linked, stomping the holy ground, repeating of the same syllables, the great hunters of the village reach for the gods with outstretched arms.

What does a 10 year old boy imagine of this place? Banned from entering, just like the women, but knowing in his heart, unlike the women, that one day he will be granted entry into the inner sanctum, a young boy of the village can only guess what goes on inside that large tent. He hears from a friend that the sorcerer sings his magic songs and calls upon the Spirit of the Reindeer, and his songs make the wind blow and the ice crack to reveal the seal below. Anxiety and yearning and fear wiggle through his body. One day he would take his place in the Quaggi and learn the secrets of the hunters.

But at fourteen an Inuit feels himself a man, and Kotuko was tired of making snares for wild-fowl and kit-foxes, and most tired of all of helping the women to chew seal-and deer-skins (that supples them as nothing else can) the long day through, while the men were out hunting. He wanted to go into the quaggi, the Singing–House, when the hunters gathered there for their mysteries, and the angekok, the sorcerer, frightened them into the most delightful fits after the lamps were put out, and you could hear the Spirit of the Reindeer stamping on the roof; and when a spear was thrust out into the open black night it came back covered with hot blood.

I should also note that I openly plagiarized the work of another composer in this piece: David Wise, who wrote all the music from Donkey Country (1 and 2). Here’s the tune I stole:

So good right?

The music from this game was the running soundtrack of my childhood. When I was in middle school, I used to pretend I was in a band (perhaps in some jazzy night club) performing this very song. This music shaped me and my compositional style. I feel honored to sample this man’s music.

The form of “Quaggi” is reminiscent of video game music. The first section is a long musical segment consisting of variations on a couple themes. It then repeats. In fact it could repeat on loop and just BE video game music.

Quiquern Part Two: The Dog Sickness

Today I finally completed part two of my piece called “Quiquern.” This movement is called “The Dog Sickness”. (Click here for part one).

I thought “Quiquern” was complete years ago. Time and again I would declare it officially finished. But then, months later, something just wouldn’t sit right with me. I’d pry it open again and tinker with its innards. Maybe it will never be done. Maybe I’m destined to dance with this score til the end of my days.

Don’t get me wrong, I have always loved this music. Every time I pick it up again, I’m reminded of why I have such a sweet spot in my heart for “Quiquern”. It evokes so many positive memories: of writing it over Christmas break in San Diego, of reading The Jungle Book over and over, of experimenting with new sounds (new to me anyways), of unhinging my creativity from purely classical harmonies and letting go a bit. Like this sort of thing:

I never go full atonal, I’m always chained in some way to classical forms and progressions, but this piece freed me up in some ways I had never tried. I went wandering a bit through the cold wilderness. I let the images in my mind solidify into a color palette. I focused on the story the sounds told, rather than fussing about the progression. This allowed me to express all the pain I felt after reading that beautiful, heart-breaking story.

So why, if this music was so compelling, couldn’t I call it “complete”? Well there were a few reasons. One is I just wasn’t thinking about form when I first wrote it. I was in “crank it out” mode, writing down whatever ideas popped into my head. I tried to free up my creative process and stop self-editing as I wrote. As a result, the music flowed pretty freely out of my brain, and the harmonies were weirder than I was used to. The musical nuggets that emerged were captivating and exotic. But there was no overarching shape to the piece. It was just idea after idea, with very little connectivity. Throwing a bunch of nuggets into a pile don’t make it a whole chicken.

This time around I wanted to work on that. This is the sort of pre-thought that Schoenberg went on about. In other words, real composers think about form and structure BEFORE writing, they don’t just wander around in the dark hoping to bump into a complete form. When I put some thought into this piece, I was able to picture the arc that I wanted to create with the music. A chaotic, hallucinogenic dream sequence, sandwiched on either side by a poignant but solitary theme calling out in the dead stillness of the ice-fields. Perhaps the middle is what the dogs feel as they begin to starve, giddy and terrified and angry; the beginning is what the Inuits feel watching their beloved animals suffer in the dark, knowing what awaits them if another source of food is not found soon. Or maybe the beginning is a song for a way of life that is slowly dying.

“What is it?” said Kotuko; for he was beginning to be afraid.

“The sickness,” Kadlu answered. “It is the dog sickness.” The dog lifted his nose and howled and howled again.

“I have not seen this before. What will he do?” said Kotuko.

Kadlu shrugged one shoulder a little, and crossed the hut for his short stabbing-harpoon. The big dog looked at him, howled again, and slunk away down the passage, while the other dogs drew aside right and left to give him ample room. When he was out on the snow he barked furiously, as though on the trail of a musk-ox, and, barking and leaping and frisking, passed out of sight. His trouble was not hydrophobia, but simple, plain madness. The cold and the hunger, and, above all, the dark, had turned his head; and when the terrible dog-sickness once shows itself in a team, it spreads like wild-fire. Next hunting-day another dog sickened, and was killed then and there by Kotuko as he bit and struggled among the traces. Then the black second dog, who had been the leader in the old days, suddenly gave tongue on an imaginary reindeer-track, and when they slipped him from the pitu he flew at the throat of an ice-cliff, and ran away as his leader had done, his harness on his back. After that no one would take the dogs out again. They needed them for something else, and the dogs knew it; and though they were tied down and fed by hand, their eyes were full of despair and fear. To make things worse, the old women began to tell ghost-tales, and to say that they had met the spirits of the dead hunters lost that autumn, who prophesied all sorts of horrible things.

Prayers to a cruel and fickle ice god.

And while I was working on form, I also put more thought into motifs. This piece has a lot of rich material, maybe even too much. Though I love that there are so many fun ideas in there, sometimes it plays like one of those Beatles songs with too many good ideas but no development. This time around I went through the piece with a needle and thread, and wove my favorite motifs into the very fabric of the piece. In and out they come, appearing and disappearing again, becoming more recognizable with each appearance. Just as a chef might pour a bit of the boiling gnocchi water into the sauce to bind all the flavors together, my goal was to bind all the ingredients of this music together into something coherent (and tasty).

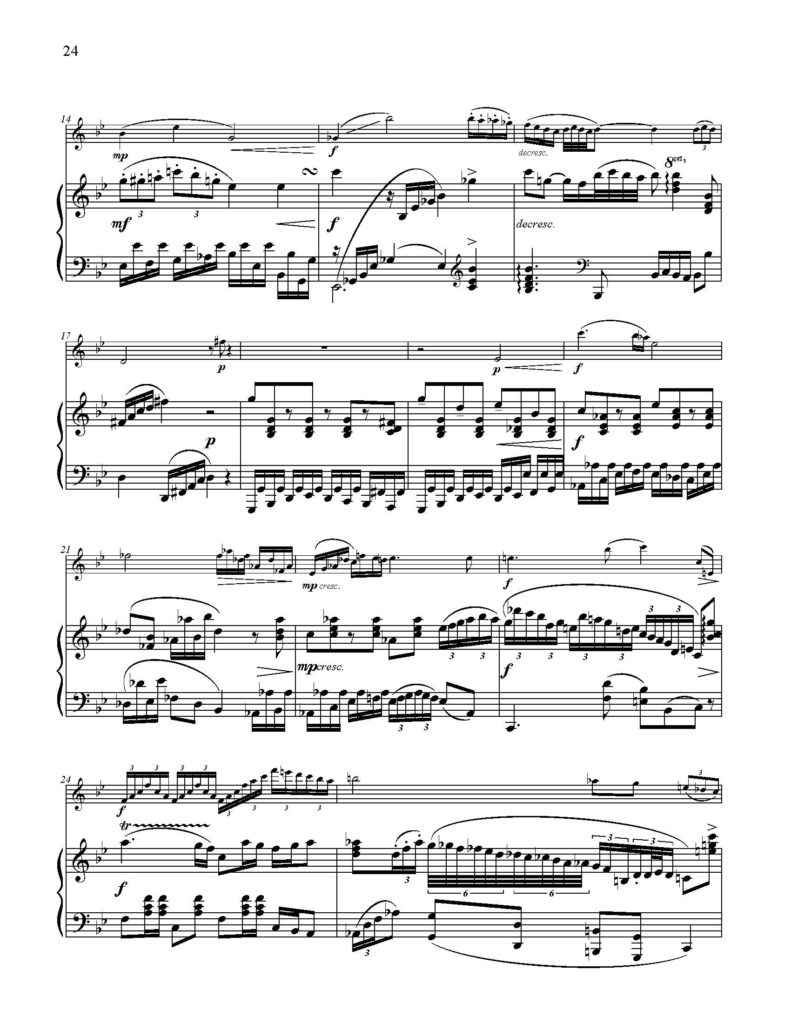

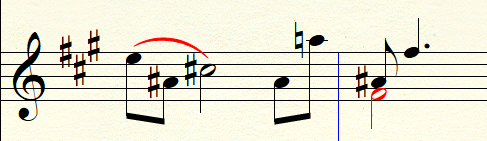

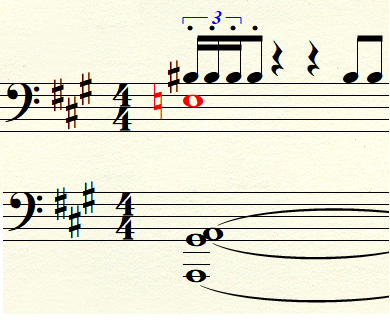

Like this motif, which appears everywhere:

Or this rhythmic motif:

There was something else fundamental that needed retooling: instrumentation. Originally I chose three flutes and piano for this piece, because the flutes evoked the lonely, frozen tundra. But as I was writing, I didn’t pay enough attention to the limitations of the flute. I wasn’t writing in an idiosyncratic way, I was just cranking out music. The used a lot of low C’s on the flute because I liked the sound, but I knew the notes were ringing out stronger in my head than they would on a real instrument, where that low C is easily covered up and lost in the mist. I considered an alto flute, but decided a clarinet would give me a whole other palette to play with.

When one phases in a new instrument like this, one can’t just paste the flute part into a clarinet staff and call it done. The addition of the clarinet changed the whole character of the piece. While the flute is cold and isolated and graceful and metallic, the clarinet is like warm baking bread. It’s also intense, frenetic, a bit insane at times, with low earthy tones that can feel angry or foreboding or subdued. That new voice greatly expanded the range of the piece, so I was able to open the music up a bit and let it breathe.

All these forces combined into something much different than the piece I’ve been kicking around all these years. This version feels like a completed piece of art. It’s not just a sketchbook of ideas, it’s a story arc with real meaning. In other words it really does feel done. For real this time. Seriously.

This music is about suffering, and in a way the audience suffers a bit as they listen. It is not over quickly. But the music is also about hope, and the idea that suffering is a part of life, and doesn’t necessarily cancel out the good. There are joyful memories mixed in with the pain. There is a dream that soon the pain will end. Yes there is fear, yes there is chaos and anger. But the sun still rises at the end, even if the air all around is frigid.

Quiquern Part One: The People of the Elder Ice

Quiquern Part One: The People of the Elder Ice.

Have a listen while you read:

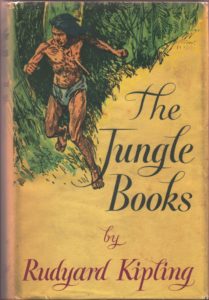

One of my favorite short stories of all time is “Quiquern” by Rudyard Kipling, from The Second Jungle Book. If you’ve never read the two Jungle Books, I highly recommend them. The Disney film only scratches a tiny surface compared to the epic stories by Kipling (Mowgli’s story is really only the first of like 20 stories). The writing is so crisp, and these stories do what all great sci-fi and fantasy stories do: they create an entire fully-formed world for the reader to explore. The world is rich and complex, and the lessons it teaches are piercing and difficult to shake.

The Disney film is fun and jazzy and hip and carefree; the written stories are raw and wild, filled with the brutal poetry of the jungle. The characters are bound by the laws of the jungle, the unwritten rules and shared understandings that guide every action the animals take. The laws dictate how to behave in times of drought, when and where hunting is permitted, and how to interact with the ever-expanding, dangerous world of Men. Only Mowgli is unbound by the laws of the jungle. Therefore he rules the jungle.

There are also so many hidden messages and deeper meanings packed into Kipling’s verse. Every story begins and ends with poems, the meanings of which change after reading each story. For example, this one:

And his own kind drive us away!

At first reading, it is a nice little poem. But after reading the story that follows it, “The Miracle Of Purun Bhagat,” the poem becomes so tragic and beautiful. Every story has these lovely little nuggets, and they make the reading experience so rich.

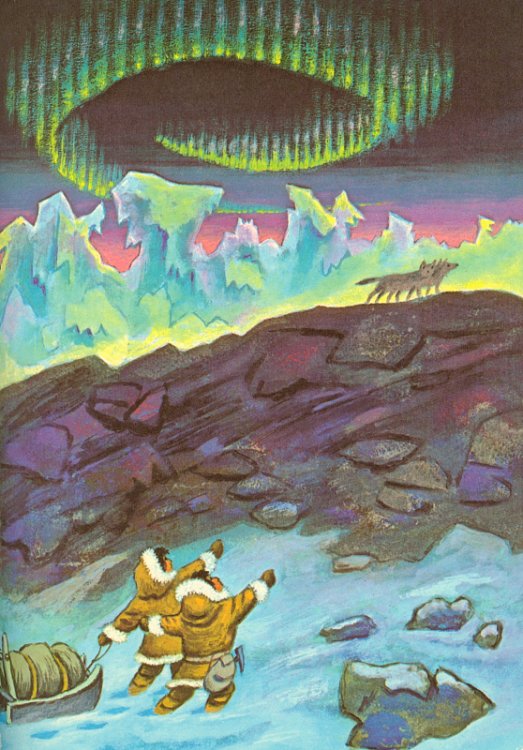

“Quiquern” is the story of a young Eskimo boy who lives in a tiny village surrounded by a frozen arctic wasteland. The village’s only source of food is seal meat which they catch with the help of their many well-trained dogs. One particular dog is born a runt, shrunken and sickly in the freezing wind. However the young boy cares for the dog, and raises him as a member of his own family. His love for the dog is pure and innocent, and together they frolic in the snow like siblings.

One year the winter is especially harsh, and the ice does not recede. The surplus seal meat runs out, and the people of the village soon begin to starve. In their moment of desperation they eat the wax from their candles, the leather from their belts. Their beloved sled dogs, still chained together in groups of eight, insane with hunger and fearing for their lives (just as lion cubs must fear their mother in times of hunger) break their chains and run screaming into the white waste. The people of the village become living skeletons.

The boy and a young girl from the village, still strong in their youth, announce to the village that they will venture out into the ice storm and find food for the village. It is suicide, but nobody stops them. Within days of their departure they are hopelessly lost, freezing, and beginning to hallucinate. They kneel shivering in the snow and announce to the heavens that they are man and wife. As darkness closes around them they pray to Quiquern, the eight-legged spider god of the arctic, for salvation and mercy.

The two children open their eyes to see a massive creature barreling toward them in the distance, eight legs scurrying effortlessly across the snow. A giant, hulking body becomes larger and larger in the morning haze. Quiquern has arrived to devour them; they are helpless as newborn seals. It is the end of their short lives, the end of their people. Two freezing, starving children prepare to die alone on a frozen plain at the edge of the world.

However as their eyes focus, they realize that the eight-legged creature is actually two dogs, running wildly through the snow pulling an empty dogsled. The dogs are well-fed and excited, blood dripping from their snouts. At the front of the pack is the runty dog the young boy once saved, frothing with joy at the sight of his oldest friend.

Carried by the sled dogs, the two Eskimos travel for miles to an open pit in the ice, where fat seals emerge for air. The dogs had found the hole in the ice and gorged themselves on meat. The boy and his wife fill the sled with food and return to the village as heroes. The village, now inhabited only by ghost-like creatures with sunken eyes, celebrates by burning whatever candles they have left. An ancient people go on.

This story burrowed down inside me and left its mark on my soul. I’m not sure why, I can’t explain it, but it filled me with the urge to write music. Originally I set out to write something eerie and cold and empty, three flutes crying out across the Arctic plain. But as I wrote, I realized it needed some bass, so I worked a piano into the mix. Years later, I switched out a flute for a clarinet to give it one more color, and that ensemble is the one that remains.

I’ve always loved my piece, Quiquern, just as I’ve always loved the story Quiquern. I can’t exactly say what it is that draws me to both, but drawn I am. Over the years I’ve written notes about this music in the margins of my journal: “Don’t forget, you love Quiquern. Don’t discard it.”

The artwork at the top of this post is by the very talented artist and sculptor Jenna Trost. Please visit http://jennatrost.com/ to see more of her lovely work.

The music you’ve been listening to is the completed first movement of this work, which is called “The People of the Elder Ice”. I hope you’ve enjoyed it. The entire middle section of this movement, which I refer to as “Village Dance,” was actually added later. Read about that addition here. For Part Two: “The Dog Sickness,”Click here.