A few years back I played keyboard for my friend Danny Saucedo on his album “Of Dream and Delirium”. You can hear the whole album below. All music is by Danny Saucedo.

Check out Danny’s other music here.

Seeking balance in a chaotic world

A few years back I played keyboard for my friend Danny Saucedo on his album “Of Dream and Delirium”. You can hear the whole album below. All music is by Danny Saucedo.

Check out Danny’s other music here.

What can I say about love? It never turns out quite the way we expect. Then again neither does life. The years stack up, and the weight of all that time compacts our experiences, until we are forged into something new, like metamorphic rock. A good marriage has the same effect. As the years pile up, any cracks that once existed between us are compressed, our minds and outlooks are reformed, until after a while we have been reshaped, remade together.

This music chases love, chases life. It races ahead, keeps the fire lit. It’s hunting, sniffing something out, hungrily searching through the night. The years fly by, but the fire stays lit. It’s a dance, a celebration, though a frenetic one.

While you listen, stomp your foot! How about one loud clap! Why the hell not!

I have a limited vocabulary for describing how it feels to experience love, real love, so I have to compose instead, to try and capture the uncapturable. This music gives just a taste of that. Love has many flavors, and this is one flavor I’ve tasted, and I want to share the feeling with the world. It may not always be pretty, but it tries hard to live passionately, to expresses itself freely, to communicate something meaningful. It doesn’t give up, even when challenges arise. It reaches out to feel a connection. It aches for it.

I have experienced this love. In fact, I experienced it today, while watching my wife walk across the room. Sometimes my heart starts pounding for no reason, and this music appears inside my brain. Makes me want to spin around and around, until everything is blurry. The life we have built, the family we created, the years and shared experiences and adventures are all stacking up before me, until all I can do is marvel at the structure.

Keep living! Keep love in your heart, and share it with someone whenever possible. Stomp and dance and spin. And also, lay silently on your bed in the afternoon with the person you love, and watch the sun’s rays poke through the blinds. Compare the sizes of your feet, tell a silly story, share what’s in your heart. Grow together, always growing.

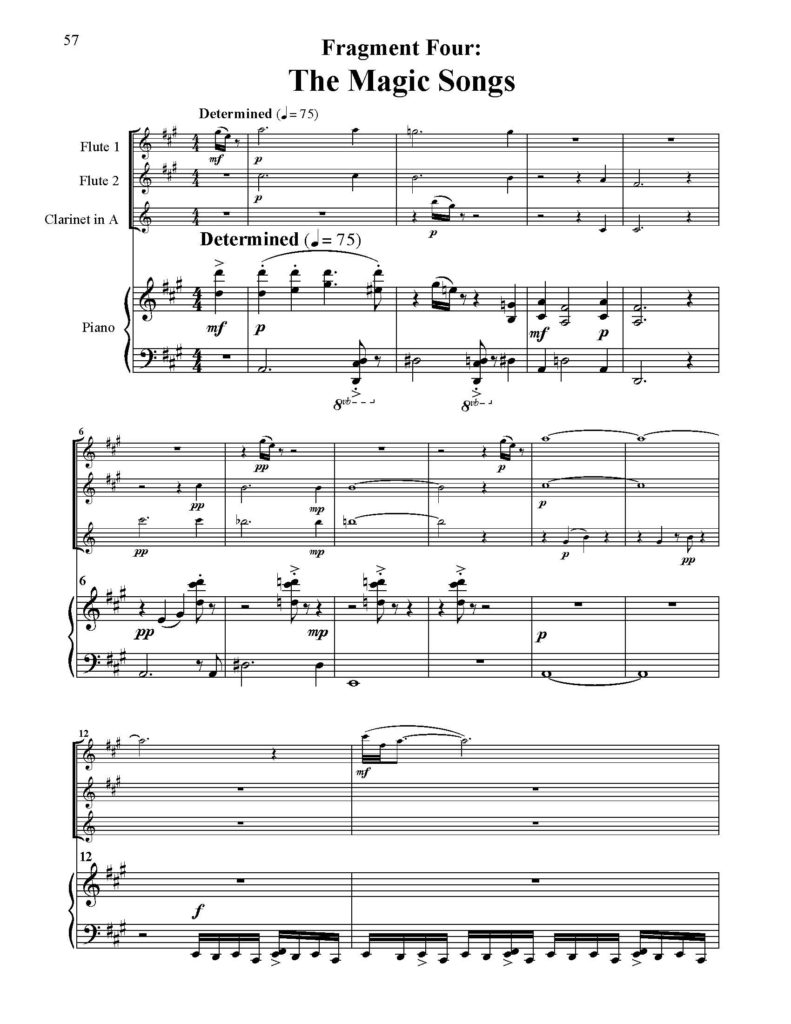

Quiquern is a five movement piece of music for piano, two flutes, and a clarinet, based on a short story by Rudyard Kipling.

Here is the story behind the music .

This next fragment of Quiquern is called “The Magic Songs”. Famished and delirious, Young Kotuko and the girl set out alone into the blizzard to find food for the starving village. As the dark and the cold and hunger devour them, the two children rave and hallucinate, unhinging themselves from the realm of men and into the realm of gods. As they descend, they sing songs of magic, songs buried deep in their memories, in their blood. Their voices rise and fall with the frozen wind.

This is the final music of Quiquern. At the end of the story, the dogs lead the boy and girl to a crack in the ice where seals are coming up for air. They kill as many seals as they can carry, and hurry them back to the village. The people rejoice as famine is averted just in time. They sing and light candles made of seal fat.

Kotuko and the girl took hold of hands and smiled,

for the clear, full roar of the surge among the ice

reminded them of salmon and reindeer time

and the smell of blossoming ground-willows.

Even as they looked, the sea began to skim over

between the floating cakes of ice,

so intense was the cold;

but on the horizon there was a vast red glare,

and that was the light of the sunken sun.

It was more like hearing him yawn

in his sleep than seeing him rise,

and the glare lasted for only a few minutes,

but it marked the turn of the year.

Nothing, they felt, could alter that.

This ending seems to think of itself as a happy ending. But that’s not really what it is. It’s not a sad ending either. The village is well-fed for today, and their way of life continues the way it has for a thousand years. There is something truly magical about that. But what happened this winter will happen again. The village’s survival is always balanced precariously upon a precipice. As the camera pans out, we are reminded that all around the happy village is an endless frozen desert, cruel and dark, and so very cold. A single warm ember in a vast field of ice.

Perhaps that is a metaphor for all of humanity. Everything that we do and everything we care about and everything we’ve ever created and everything we remember and cherish is but a tiny ember in the blackness of space. How hard we all try to keep it lit; how vast and cold and uncaring is the universe.

Does that mean we shouldn’t live our lives to the fullest? Of course not! It’s even more reason to appreciate life. The feel of a baby’s skin on one’s cheek, the laughter of a life-long friend, the warm embrace of a lover, the taste of well-prepared food, the memories of good times, the hopes and dreams and aspirations we all nurture in our hearts; these things keep us warm and snug through the winters of life, even if deep down we know that the dark need not attack us directly to see us finally defeated, it need only wait.

This evening I added the finishing touches to a piece I composed back in 2008, “A Letter to My Father.”

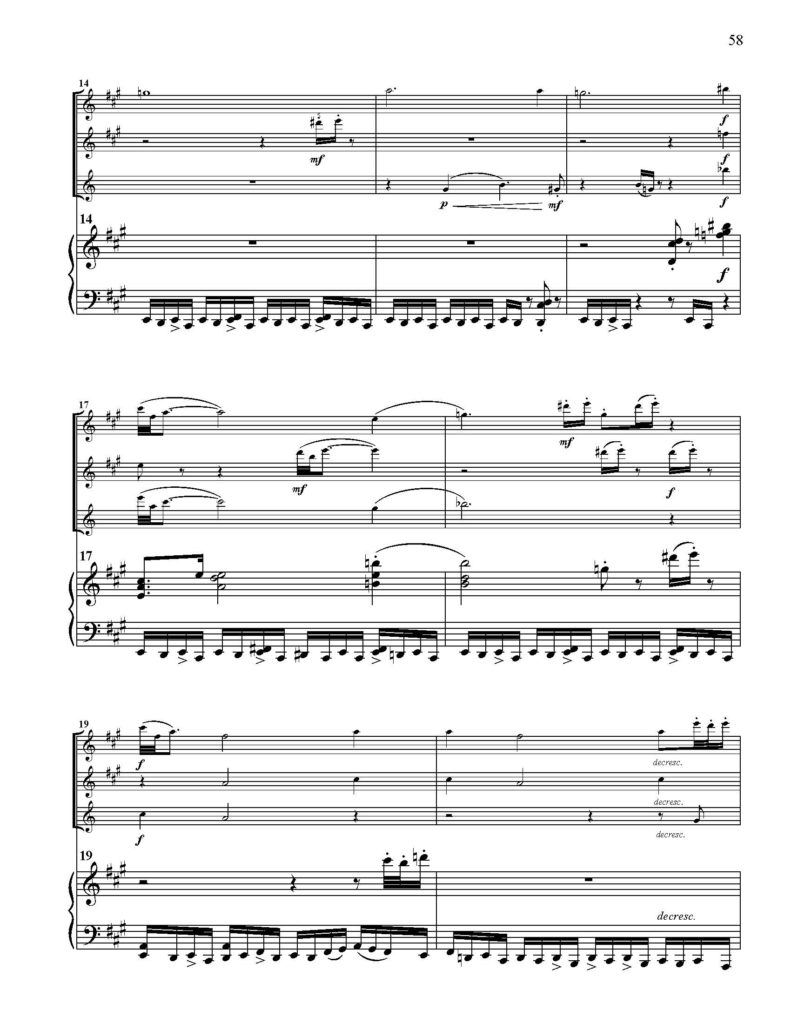

This piece is actually the third movement from my string quartet “Jackdaw.” Therefore at its heart it is based on the life and writings of Franz Kafka, like all the other music in that quartet. However this music has special meaning for me as well (also like all the music in that quartet). It feels especially meaningful during this current time in my life, when my own interactions with my father have become so very strange.

When Kafka was about 36, he wrote a nasty letter to his dad. Apparently his father Hermann was a pretty difficult guy, constantly ridiculing Kafka for being a weakling, while refusing to care one bit that his son was a genius. Kafka’s stories are real mind-benders. The realities they portray are just “off” enough that they feel like they could be real life. One can recognize the landscape, envision oneself living in that world, but something in the reality is very wrong. Sometimes it’s hard to put one’s finger on… but impossible to ignore. Like the work of H.P. Lovecraft, the stories have the power to make one doubt one’s own world, to make one doubt mankind as a whole. It’s delicious writing, and frankly still horrifying to this day. Despite young Franz’s clear talent, Poppa Kafka just didn’t respect his son, and he made that known at every opportunity.

By age 36, Franz was tired of Hermann’s crap. He busted out some paper and really let Dad have it, for 45 hand-written pages. In his own way, Kafka believed that this letter would help heal their relationship, but in reality the letter was full of complaints, accusations, and invective. He plumbed the depths of his own hurt, and wrung the emotions out onto the page. If the letter is to be believed, Hermann was a toxic and narcissistic hypocrite, an abusive tyrant who never gave his fragile son even a kindly word or friendly look in all his life. The writing is heart-breaking and so very relatable, ripe as it is with a certain timeless pain that has been felt by so many sons across so many generations.

In one episode, Kafka describes a traumatizing experience from his childhood: one evening at bedtime he was begging his father for some water (perhaps even being a bit bratty about it), when his father, always a large and intimidating man, burst into his bedroom without warning and, in a rage, grabbed the small boy and locked him outside on the balcony with nothing on but his thin cotton sleep shirt. Kafka writes:

I was quite obedient afterwards at that period, but it did me inner harm. What was for me a matter of course, that senseless asking for water, and the extraordinary terror of being carried outside were two things that I, my nature being what it was, could never properly connect with each other. Even years afterwards I suffered from the tormenting fancy that the huge man, my father, the ultimate authority, would come almost for no reason at all and take me out of bed in the night and carry me out onto the balcony, and that meant I was a mere nothing for him.

Franz Kafka, from Letter to His Father

Not only is this a sad story of parental mismanagement and emotional scarring, but it is also such a great insight into why so much of Kafka’s writing features nameless, faceless authority figures who carry out irrational sentences with a total lack of empathy or emotional connection. Moments that feature characters like that are some of the more disturbing vignettes from his stories; they make it all too easy to picture oneself being dragged away by faceless agents of the state who have no sense of human morality or concern for life. Kafka was able to translate his tragic daddy issues into terrifying metaphors for what it’s like to live in modern society. Now THAT’S how to cope with a bad upbringing.

Funny story: I had to send a letter to my own father recently. Mine was not as nasty as Kafka’s, nor was my father anywhere near as abusive as Hermann. But father-son relationships can be all varieties of strange, and mine definitely falls on that spectrum. I won’t go into the details here, but suffice it to say that at pretty much the same age as Kafka when he wrote his letter, I felt compelled to write a letter to my dad that I wish I didn’t have to write. It delivered the message, though I’m not sure it did anything to heal our relationship.

When Kafka completed his letter, he hand delivered it to his mother, and asked her to bear the letter to his father. Her mother read it once and immediately decided to hide it forever. As much as Kafka might have hoped his manifesto would help heal old wounds, his mother felt differently, and refused to take any part in provoking the monumental explosion that would likely follow should Hermann ever read it. My own letter was delivered directly to my father, though I’m actually not sure he read it. One can never know these things when direct communication becomes impossible.

Long story short, this music ain’t just about Kafka. I hope someday someone writes about how I skillfully took my familial pain and transformed it into timeless art we can all relate to. Whether or not that ever happens, I will say this: writing the music always makes me feel better.

One time I let myself fall. Down, down, down into the mud I went, slowly, ever so slowly, until my head was under, and I was lost for a time.

by Garrett Mattingly

by Jay L. Garfield

by Ramachandra Guha

by Michael Wysession

by Herodotus

by Frances Stonor Saunders

by Cecil Woodham-Smith

This book was so moving, it inspired me to make this series on the Irish potato famine:

by Cecil Woodham-Smith

edited by Terrell Carver

by Melvin Konner

by Thomas Asbridge

by Dan Jones

By James McPherson

by Steven Pollock

by Yuval Noah Harari

by Leszek Kołakowski

This book is a masterpiece of philosophical summary and deep-diving analysis. Kolakowski has an uncanny ability to break down and explain even the most complex philosophical arguments in a clear and concise manner. At times he plays the part of omniscient referee, diligently sorting the good ideas from the flawed ones. But never does he simply tell us that a writer’s theory is wrong; instead he identifies the holes in it and pries them open, exposes them to the light, lets the reader decide what to think.

In this book his main target is Leninism, a philosophical tradition absolutely bursting with contradiction and double-talk. Kolakowski’s even-handed tone and mind-bogglingly high level of erudition suggest that he did not intend to write a polemic against Leninism. But in the end Kolakowski’s even-handed philosophical critique of Leninism amounts to a withering indictment of Lenin’s method, his philosophical rigor, his honesty, and his contradictory actions once in power. Lenin is revealed to be a boor, a liar, a tyrant, a power-hungry despot. Kolakowski does not draw these conclusions explicitly, but instead allows the reader to do so. Perhaps Kolakowski is a masterful propagandist who possesses the ability to incept these opinions into the reader’s brain, but I don’t really believe that. Instead he just exposes various thinkers’ theories to the light, that’s all. This doesn’t mean Kolakowski is a constant critic; his analysis is so much more subtle and productive than that. If a theory has enough qualities to withstand the author’s scrutiny, it comes out stronger for it in the end. Kolakowski analyzes many Marxist ideas and traditions throughout his magnum opus, and a good portion of them – those based on sound reasoning, honest argumentation, and deep philosophical reflection – show their quality under Kolakowski’s scrutiny. It just turns out that when we shine this same light on Lenin’s theories, they wither, crack, and fall apart. They are revealed to be hollow and decrepit. (Oh dang I’m being too polemical again).

Kolakowski sees Lenin’s dismantling of Soviet democracy as the original sin of Bolshevism. Lenin’s critique of bourgeois democracy hinged on the notion that modern democracy is a sham: the propertied classes (who overwhelmingly benefit from capitalism and bourgeois law) trick the exploited masses into believing they are sovereign in order to pacify them and prevent revolution, though in reality the workers are largely disenfranchised. In other words, the masses are led by our culture, media, and propaganda (all of which is shaped by the ruling class) to believe in freedom, democracy, individualism, and the sanctity of private property, but all of that is a veil over their eyes that prevents them from noticing that they are slaves. This sentiment, borrowed wholesale from Marx, is compelling in itself. Here’s the sad irony: once in power Lenin banned all democratic expression (including dissent from the proletarians he claimed to speak for), imprisoned his political adversaries, and disallowed any political party but his own. A man who rose to power by arguing that only communism could bring authentic democracy to the masses turned out to be a despot who was so desperate to hold on to power that he fully and permanently disenfranchised the masses. To make it worse, while doing so he claimed that the new Soviet system was a more authentic form of democracy than a parliamentary system could ever be. Kolakowski punishes Lenin for this betrayal of his own principles, simply by laying out the actual actions Lenin took once in power. Turns out that listing Lenin’s achievements is enough to reveal his naked opportunism and staggering hypocrisy.

Kolakowski’s main argument, if one must be identified, is that Bolshevism did not deteriorate into totalitarianism because of Stalin (as is often argued, especially by Lenin sympathizers), but instead because totalitarianism was baked into Lenin’s philosophy from the start, despite all the noises he made about wanting to create a better democracy. Before he was even in power, Lenin fantasized about liquidating all his political opponents, using violent coercion to keep all dissenters in line, and dictating to the masses what was and was not in their best interest. He desired to create a new permanent elite (the communist party officials), but dressed it up as if he was actually abolishing all elites forever, as if his new elite would better represent the masses than could parliamentary democracy. Lenin described in detail his dream of conducting mass confiscations of all private land and surplus (see Lenin’s State and Revolution), and imagined that the bulk of the people would not only celebrate these actions but assist in the mass thievery. In reality, Lenin’s first economic policy of requisitioning “surplus” grain from peasants (or what the requisitioners considered to be surplus) led to widespread mistrust of Lenin’s new state, as well as bribery and coercion. The people did not want to give up their product to the state, and the officials in charge of snatching the goods were highly susceptible to bribes. Their only carrot for making the people obey was threat of force, and use of Lenin’s massive police state infrastructure. Meanwhile all political activity that did not “further the socialist revolution” was anathematized.

This was not Stalinism, but Lenin’s original ideas and policies, the tactics that he used when he (Lenin) was in charge. Modern lovers of Lenin argue that he truly fought for the good of the people, and that after his death it was Stalin who corrupted his ideas and policies, warping them into a totalitarian, violently repressive, hyper-bureaucratic police state. But Lenin was the true founder of Soviet totalitarianism. Kolakowski lays this bare without becoming overly angry in the process (something I would struggle with). In the end, his critique of Lenin is devastating, yet really he lets most of Lenin’s ill-conceived ideas and shameful policies speak for themselves.

Want more book recommendations? Go here.

The date was September 24, 2006, my 22nd birthday. Erica and I decided to have a picnic in Meadow Park, share a bottle of wine, and take a nap. It was during this wine-induced nap that somebody walked into our house, in the middle of the day no less, while we slept peacefully in the bedroom, and stole my laptop.

This particular laptop happened to contain all the music I had ever written up to that time. Was it backed up somewhere? Of course not. After all, my laptop had never been stolen before, so why would I need to back up everything I’d ever created. Nope, it was all right there, and someone stole it right out of my house in broad daylight. I never saw it again.

The thief did not take our DVD player. He did not take our television. He did not take my car keys or the stereo either. He didn’t even take the laptop’s power cord. Just the laptop. And of course my very reason for living.

When I awoke from my cat nap, it took me a good half hour to realize the laptop was gone. I won’t try to put into words what went through my head except to say this: all of my art was destroyed that day. I had no website, no hard drive, no printed copies. I felt like a victim of fire. I was completely alone with my grief.

Ok I was able to salvage a couple things. While ravaging through my belongings looking for any sheet music I could find, I miraculously discovered some printed pages stuffed down into a drawer. The pages were the original versions of what would later become the 3rd and 4th movements of my first piano sonata. I was also able to copy down from memory the scraps that would later become the last movement of my first string quartet. Other than those tidbits, everything else was taken forever. My entire career as a composer up to that point was a blank page.

It took me a long while to get into the headspace of composing again. When I finally did, for some reason this jolly music is what came out. Maybe it was the sense of hope that even though I had lost all my previous work, I could still write something new, that my life as a composer was not actually over. As I continued to write this, my hope only continued to grow. By the time it was done, there was a part of me that was glad I had lost my old work, which is a weird thing. In a way, it was a freeing experience to lose my student work. It allowed me to try new things, and not feel weighed down by whatever direction I had chosen in the past. I think that’s what this music is trying to say.

Excerpt from journal.

Dated July 27, 2012 – Prague

On a recommendation from a bartender, we headed toward a pub away from the city center, on some twisted alley or another. Our bellies were full of dumplings and gravy, our hearts starving for adventure. We waltzed into a well-lit bar and took a drink of the scenery.

The air was viscous with cigarette smoke. I immediately felt as though I were deep deep underwater, in a pub at the bottom of the sea. The rowdy conversations of the crowd drifted slowly toward me; from a distance I could see the words coming my way, yet still I couldn’t quite make them out. Men and women emphatically slapped the tables in laughter, rattling the half empty glasses and late night coffees and honey cakes, sending them floating away around the room. Others sipped their absinthes knowingly, balancing their cigarettes so delicately atop their outstretched fingers.

Ah Prague, ah absinthe. In honor of Bohemia we ordered two drams of the green concoction. Actually it wasn’t green… but it did smell like licorice, and it burned, burned!

It suddenly became very warm in that bar.

I was taking in my hazy surroundings when I saw her, sitting silently beside a red couch. She wasn’t outlandish, wasn’t putting herself out there, just relaxing and blending into the scenery. I’m not sure anyone else in the room even noticed her.

She was a thing of beauty.

She had a strong yet elegant frame made of fine wood panels. Her golden pedals glimmered and winked at me, beckoning me. Her keys were made of real ivory, an authenticity that can not be faked. This was no tourist attraction. This was the real shit, the soft underbelly, the pearl, that hard-to-reach part of your back. I was suddenly helpless against a mighty river of desire. I let it take me, wash over me, sweep me away.

I could tell right away that she was played regularly; all the tell-tale signs were present. The keys were bare and open for all the world to see, draped flirtatiously like freshly painted fingernails. The bench was pulled out, a bare leg peeking from beneath a knee-length skirt. However refined she may have seemed to an untrained eye, I could see from across the room how much she loved to be touched, that her strings were tight, her music sweet and pure.

I realized I was in a conversation with a man at the bar. While pretending to chat, my gaze kept wandering to her quiet corner of the room. She stared back at me unabashed. I wanted to put my hands on her that very moment, to know her secrets.

Erica looked at my face and read me like a book. I was lost already and there was no point trying to pull me back. We locked eyes and she signaled that I was free to go. I immediately moved to the instrument.

When I touched, I fell into a trance. Twenty minutes of absinthe-fueled dream music left my body.

Dumplings and cigarettes and alleyways. Twisting streets and beggars with their faces in the dirt. Pianos and absinthe and my wife’s soft skin. Love and travel and hunger and… feeling so lost that you forget what country you’re in.

I learned this recipe in Rome. This dish tastes super gourmet, but it’s actually very easy to make if you give the sauce the time it needs to fully mature. Serve this dish to your friends, and forever after you will be able to make them call you “chef”.

For this recipe, the quality of ingredients is very important. Try to get yourself to an authentic Italian grocery store if you can. Guanciale might be difficult to find, but can be substituted with pancetta if need be. If you can’t find that, thick bacon is ok as long as it isn’t smoked. If you have the time, you could also make your own guanciale, assuming you have a whole pig’s head lying around. The gnocchi should be freshly made if possible.

Ingredients

3 thick slices of guanciale (pork made from pig jowls), chopped into small cubes

EVOO

1 small onion, chopped

Chopped mushrooms

Hot red pepper flakes

One can of whole tomatoes with juices (again, choose a can with no added preservatives, as natural as possible)

1 pound of potato gnocchi

Fresh basil

1 half jar of filleted anchovies packed in oil

1/2 cup grated Romano cheese

Directions:

“Quiquern” is a short story from Rudyard Kipling's Second Jungle Book.

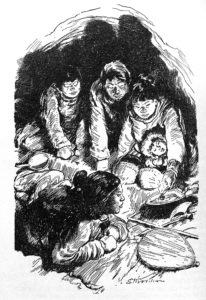

A young Eskimo boy lives in a tiny village surrounded by a frozen arctic wasteland. The village’s only source of food is seal meat which the people catch with the help of their many well-trained dogs. One particular dog is born a runt, shrunken and sickly in the freezing wind. However the young boy cares for the dog, and raises him as a member of his own family. His love for the dog is pure and innocent, and together they frolic in the snow like siblings.

One year the winter is especially harsh, and the ice does not recede. The surplus seal meat runs out, and the people of the village soon begin to starve. In their moment of desperation they eat the wax from their candles, the leather from their belts. Their beloved sled dogs, still chained together in groups of eight, insane with hunger and fearing for their lives (just as lion cubs must fear their mother in times of hunger) break their chains and run screaming into the white waste. The people of the village become living skeletons.

The boy and a young girl from the village, still strong in their youth, announce to the village that they will venture out into the ice storm and find food for the village. It is suicide, but nobody stops them. Within days of their departure they are hopelessly lost, freezing, and beginning to hallucinate. They kneel shivering in the snow and announce to the heavens that they are man and wife. As darkness closes around them they pray to Quiquern, the eight-legged spider god of the arctic, for salvation and mercy.

The two children open their eyes to see a massive creature barreling toward them in the distance, eight legs scurrying effortlessly across the snow. A giant, hulking body becomes larger and larger in the morning haze. Quiquern has arrived to devour them; they are helpless as newborn seals. It is the end of their short lives, the end of their people. Two freezing, starving children prepare to die alone on a frozen plain at the edge of the world.

However as their eyes focus, they realize that the eight-legged creature is actually two dogs, running wildly through the snow pulling an empty dogsled. The dogs are well-fed and excited, blood dripping from their snouts. At the front of the pack is the runty dog the young boy once saved, frothing with joy at the sight of his oldest friend.

Carried by the sled dogs, the two Eskimos travel for miles to an open pit in the ice, where fat seals emerge for air. The dogs had found the hole in the ice and gorged themselves on meat. The boy and his wife fill the sled with food and return to the village as heroes. The village, now inhabited only by ghost-like creatures with sunken eyes, celebrates by burning whatever candles they have left. An ancient people go on.