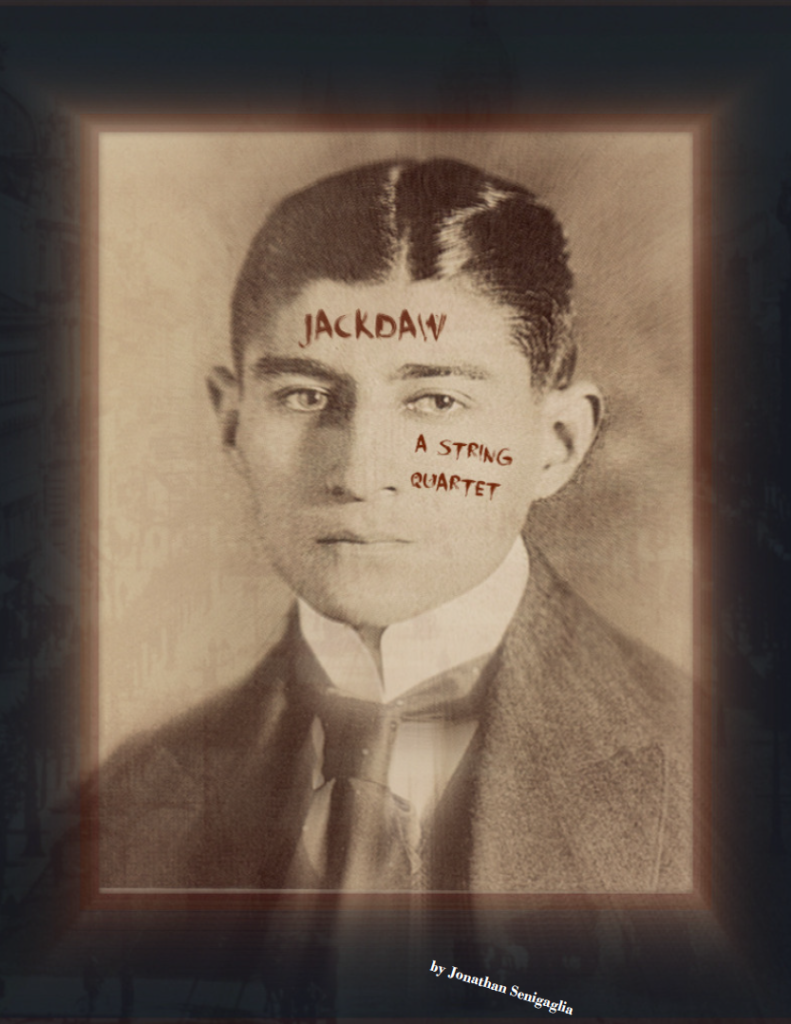

When I was a young man of 22, I developed a bit of an obsession with Franz Kafka. In retrospect this feels like a natural thing to have happened, since Franz Kafka’s stories are basically angst incarnate, and I was certainly feeling a whole lot of angst at age 22. At the time, I was a recent college graduate working at Borders, resisting my parents’ urgings to go get a teaching credential and start my career. I was broke, uncertain whether I was a kid or a grown-up, terrified of the future, maladjusted to the world around me, and dissatisfied with who I was. So yeah, Kafka spoke to me.

In Kafka’s world, nameless police break into your home in the middle of the night and drag you to your trial, where none of the evidence makes any sense to you but the judge sentences you to death anyhow. Kafka’s characters react to things differently than we would expect normal humans to react, which creates a disorienting feeling that something is off, or that we just don’t understand the rules. These vibes made me feel right at home in my early 20s, when I felt the profound sensation that I did not understand the world, that I did not know all the rules, that something was a bit off.

The Metamorphosis is the ultimate story for this brand of angst. The main character (who is pretty much Kafka himself) awakes to find he has become an enormous insect, a disgusting vermin, a horror so hideous his family can’t even look upon him. Like his family, he doesn’t understand why this has happened to him, or why, or even what kind of food he is supposed to eat to stay alive. When his family leaves plates of food inside his door, the food just makes him sick. He can’t communicate with anyone. Nothing makes sense. He spends his time frantically scuttling up and down the walls trying to make sense of the world, staring out the window longingly, and listening to his sister play heartbreaking melodies on her violin from the other room. His family tries to live normal lives, but clearly everyone has been shattered by the transformation. In the end, the bug dies. The family sweeps the corpse out of the house, and go out together to buy new clothes. Now that the horrible freak is gone, they feel alive again.

I think this story is really about feeling misunderstood. For anyone who has ever felt directionless, or lacking in strong relationships, or “apart” from the world, this story creates a perfect little metaphor for how that feels. You feel like a disgusting bug that can’t communicate, doesn’t understand how the world works, and just weirds people out. For all the sci-fi/horror components of the story, it’s really about the author himself feeling hurt and alone. Kafka, though brilliant, was a pretty misunderstood guy in his time. His low self esteem was reinforced by his brutish father, who never gave a kind word or loving gesture to his only son. Young Franz, a sickly but gifted kid, seemed unable to relate to most of the people around him, as if he came from a different culture (or planet). Easy to imagine him picturing himself as that bug. I know I did the same back when I felt so lost.

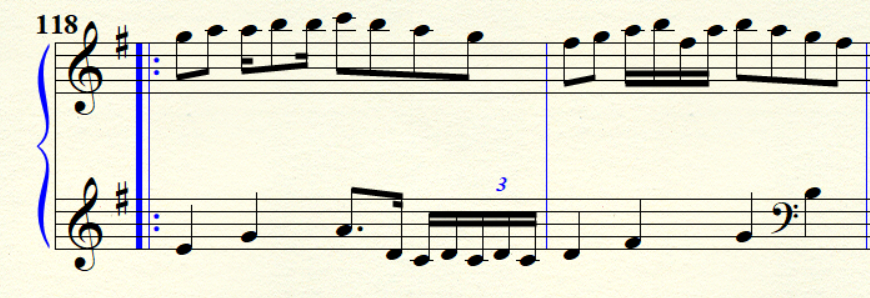

The music itself is a rondo, which looks like this:

The curtain raises on the reflective and somber “A” theme, music that comes back again and again throughout the piece. It’s a theme song (if you will) for the giant hideous bug monster pondering his own fate. The “B” section is the bug coming to terms with his new reality. He grieves and questions and rages and hopes and longs for things to be different. But inevitably that “A” section returns, confirming that this horror show truly is his reality, and resignation sets in. In the “C” section, the bug realizes that, though he is a monster unloved by the world and locked forever in his room, when he sets his humanity aside and embraces his bug-ness, he can do some cool stuff. He scurries up and down the walls, forgetting himself in the joy of stretching his segmented, hairy bug legs. It isn’t so tragic, at least for the moment, that he is no longer a man. He explores his bug senses, listening and smelling and experiencing his new reality, feeling what could even be described as happiness. He isn’t trying to be human or trying to be loved, but just being whatever he is.

In this music, there is a moment in the middle, while the bug is happily scurrying all over the walls, when suddenly you can hear his sister’s violin ringing through, her gentle tune rising above everything else, nostalgic and sad as the memory of a lost love. He may be separated from her, unable to communicate, horrifying to look upon, but they both understand that melody for what it is: a love song. Even in the midst of pain and uncertainty and fear, there are still things that tie us all together. One of those is love. Another is music.