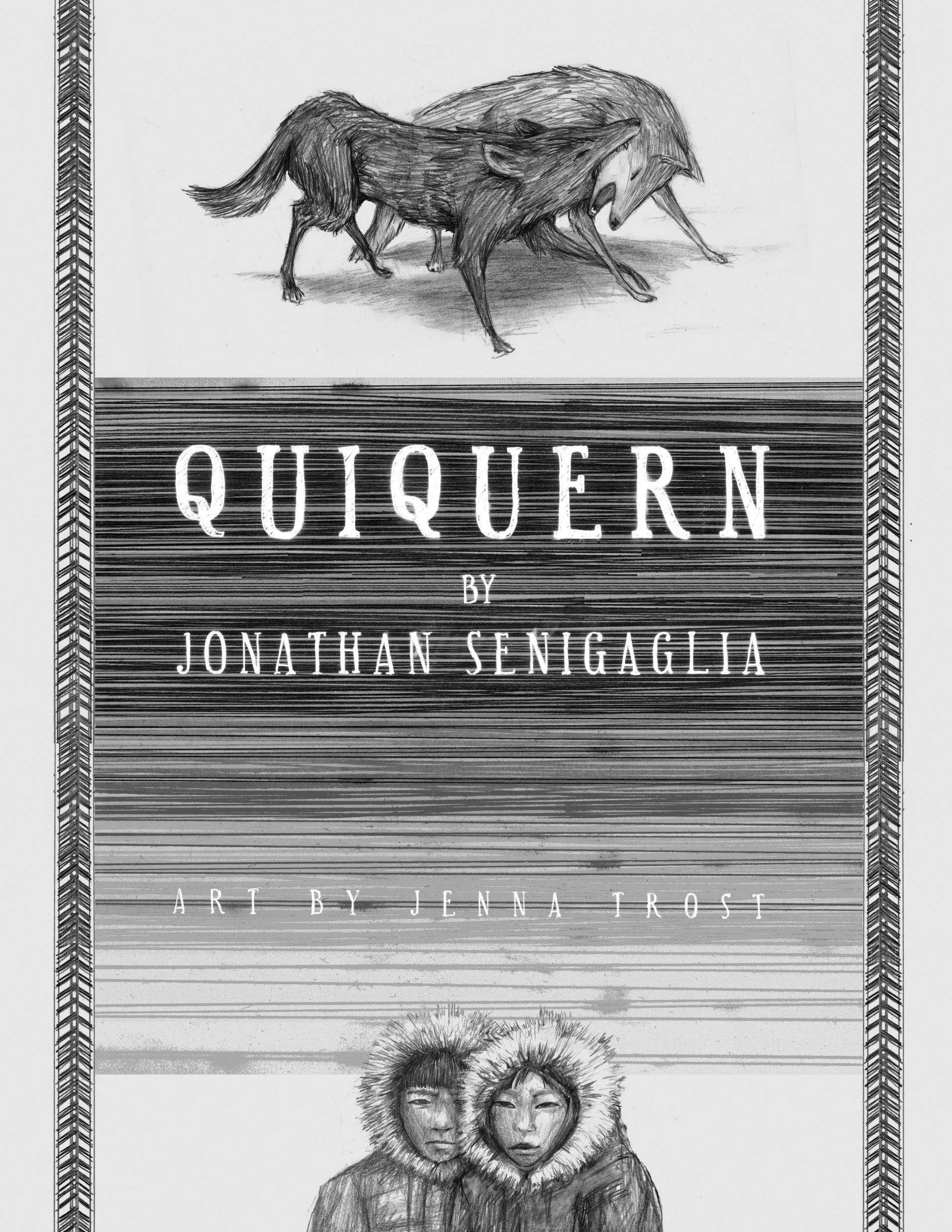

Quiquern Part One: The People of the Elder Ice.

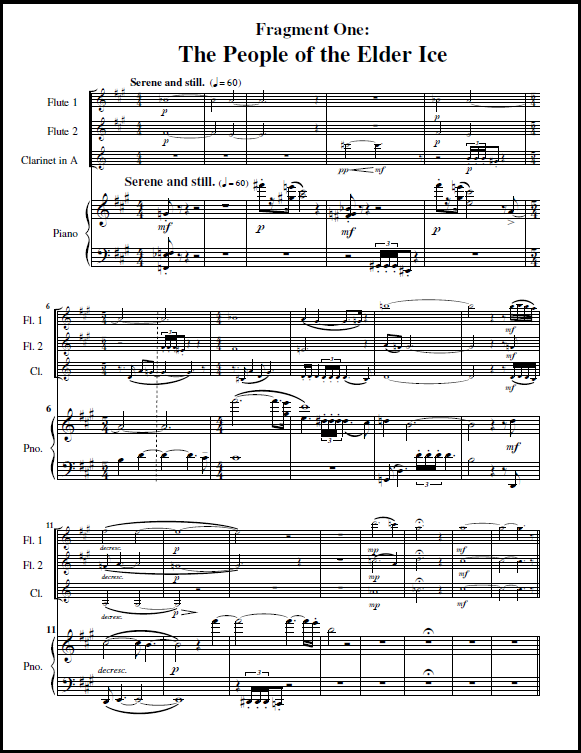

Have a listen while you read:

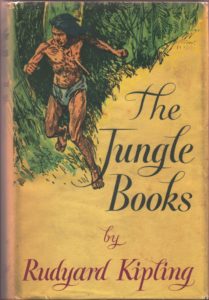

One of my favorite short stories of all time is “Quiquern” by Rudyard Kipling, from The Second Jungle Book. If you’ve never read the two Jungle Books, I highly recommend them. The Disney film only scratches a tiny surface compared to the epic stories by Kipling (Mowgli’s story is really only the first of like 20 stories). The writing is so crisp, and these stories do what all great sci-fi and fantasy stories do: they create an entire fully-formed world for the reader to explore. The world is rich and complex, and the lessons it teaches are piercing and difficult to shake.

The Disney film is fun and jazzy and hip and carefree; the written stories are raw and wild, filled with the brutal poetry of the jungle. The characters are bound by the laws of the jungle, the unwritten rules and shared understandings that guide every action the animals take. The laws dictate how to behave in times of drought, when and where hunting is permitted, and how to interact with the ever-expanding, dangerous world of Men. Only Mowgli is unbound by the laws of the jungle. Therefore he rules the jungle.

There are also so many hidden messages and deeper meanings packed into Kipling’s verse. Every story begins and ends with poems, the meanings of which change after reading each story. For example, this one:

And his own kind drive us away!

At first reading, it is a nice little poem. But after reading the story that follows it, “The Miracle Of Purun Bhagat,” the poem becomes so tragic and beautiful. Every story has these lovely little nuggets, and they make the reading experience so rich.

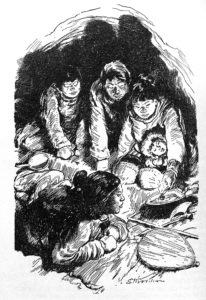

“Quiquern” is the story of a young Eskimo boy who lives in a tiny village surrounded by a frozen arctic wasteland. The village’s only source of food is seal meat which they catch with the help of their many well-trained dogs. One particular dog is born a runt, shrunken and sickly in the freezing wind. However the young boy cares for the dog, and raises him as a member of his own family. His love for the dog is pure and innocent, and together they frolic in the snow like siblings.

One year the winter is especially harsh, and the ice does not recede. The surplus seal meat runs out, and the people of the village soon begin to starve. In their moment of desperation they eat the wax from their candles, the leather from their belts. Their beloved sled dogs, still chained together in groups of eight, insane with hunger and fearing for their lives (just as lion cubs must fear their mother in times of hunger) break their chains and run screaming into the white waste. The people of the village become living skeletons.

The boy and a young girl from the village, still strong in their youth, announce to the village that they will venture out into the ice storm and find food for the village. It is suicide, but nobody stops them. Within days of their departure they are hopelessly lost, freezing, and beginning to hallucinate. They kneel shivering in the snow and announce to the heavens that they are man and wife. As darkness closes around them they pray to Quiquern, the eight-legged spider god of the arctic, for salvation and mercy.

The two children open their eyes to see a massive creature barreling toward them in the distance, eight legs scurrying effortlessly across the snow. A giant, hulking body becomes larger and larger in the morning haze. Quiquern has arrived to devour them; they are helpless as newborn seals. It is the end of their short lives, the end of their people. Two freezing, starving children prepare to die alone on a frozen plain at the edge of the world.

However as their eyes focus, they realize that the eight-legged creature is actually two dogs, running wildly through the snow pulling an empty dogsled. The dogs are well-fed and excited, blood dripping from their snouts. At the front of the pack is the runty dog the young boy once saved, frothing with joy at the sight of his oldest friend.

Carried by the sled dogs, the two Eskimos travel for miles to an open pit in the ice, where fat seals emerge for air. The dogs had found the hole in the ice and gorged themselves on meat. The boy and his wife fill the sled with food and return to the village as heroes. The village, now inhabited only by ghost-like creatures with sunken eyes, celebrates by burning whatever candles they have left. An ancient people go on.

This story burrowed down inside me and left its mark on my soul. I’m not sure why, I can’t explain it, but it filled me with the urge to write music. Originally I set out to write something eerie and cold and empty, three flutes crying out across the Arctic plain. But as I wrote, I realized it needed some bass, so I worked a piano into the mix. Years later, I switched out a flute for a clarinet to give it one more color, and that ensemble is the one that remains.

I’ve always loved my piece, Quiquern, just as I’ve always loved the story Quiquern. I can’t exactly say what it is that draws me to both, but drawn I am. Over the years I’ve written notes about this music in the margins of my journal: “Don’t forget, you love Quiquern. Don’t discard it.”

The artwork at the top of this post is by the very talented artist and sculptor Jenna Trost. Please visit http://jennatrost.com/ to see more of her lovely work.

The music you’ve been listening to is the completed first movement of this work, which is called “The People of the Elder Ice”. I hope you’ve enjoyed it. The entire middle section of this movement, which I refer to as “Village Dance,” was actually added later. Read about that addition here. For Part Two: “The Dog Sickness,”Click here.