“I see you more clearly, the movements of your body, your hands, so quick, so resolute, it’s almost like a meeting; even so, when I then want to raise my eyes to your face, in the middle of the letter… fire breaks out and I see nothing but fire.”

Franz Kafka in a letter to Milena Jesenska

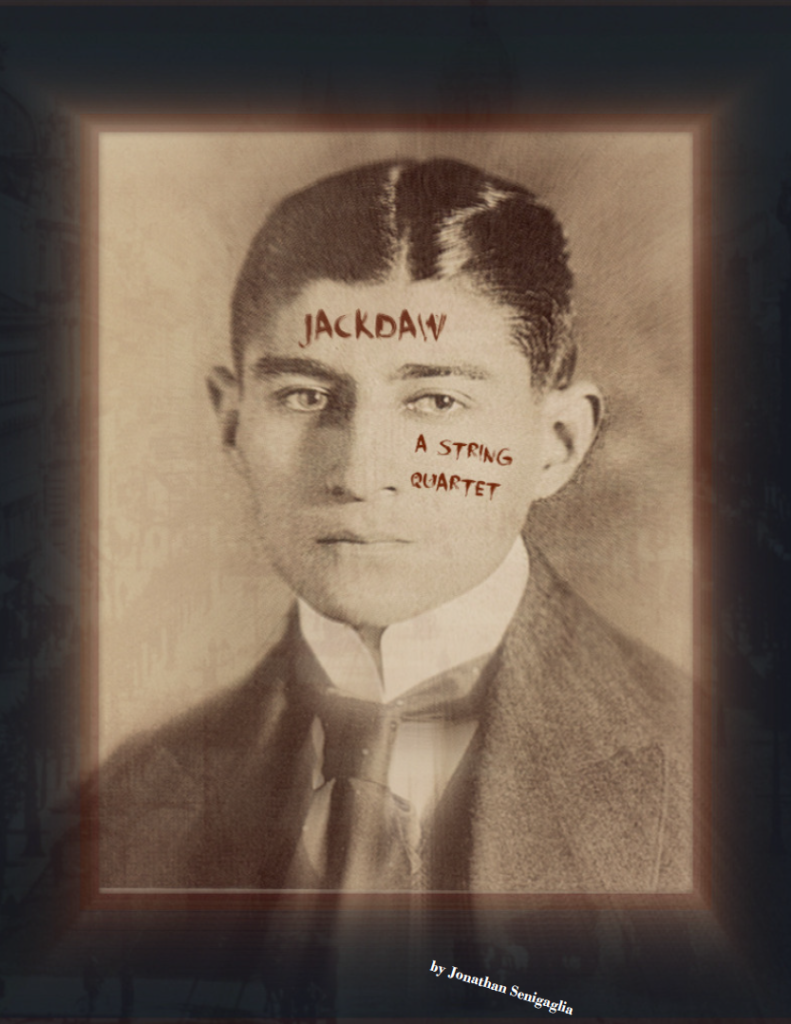

Franz Kafka began writing letters to Milena Jesenska when he was on holiday recovering from Tuberculosis in 1920. It began as a business correspondence; she was a translator of his short stories, and in addition to that, a married woman living in far away Vienna. However what began as a professional relationship soon warped into an obsessive kind of long-distance romance. The letters from Kafka are infused with desperate passion and lust, a sleepless, jagged, stream of consciousness urgency to every sentence he wrote. He wanted to worship her, to kiss her feet. He wanted to hold her from all sides, to steal her in the night and make love to her in the dark forests outside Vienna. He was guilt-ridden and embarrassed one moment, triumphantly confident of his love for her the next moment. He wanted her to take away his pain and disease, to see him for who he was and accept him, to want him. His love was insistent and oppressive and private.

Of course, this affair was doomed. She was a married woman living far away. Kafka was dying and desperate for love. Over the course of their entire affair, they only met in person twice. So really, the letters weren’t just a part of their relationship; the letters were their relationship. Kafka clearly obsessed over every word she wrote. He poured his very soul onto every page. He kindled the flame for as long as he could, but eventually he couldn’t stop Milena from breaking off the affair.

Milena preserved Kafka’s letters, and understood him as a genius. When Kafka died she wrote a loving obituary in the Vienna press, and promoted his works. Later, when the Nazis came, she joined the resistance and helped many Jews escape Austria, though the work was dangerous and she was not Jewish. Eventually the Nazis arrested Milena for consorting with Jews, and sent her to Ravensbruck Concentration Camp where she died in 1944.

“By the way, why am I a human being, with all the torments this extremely vague and horribly responsible condition entails? Why am I not, for example, the happy wardrobe in your room, which has you in full view whenever you’re sitting in your chair or at your desk or when you’re lying down or sleeping… Why am I not that?”

Franz Kafka in a letter to Milena Jesenska

“Yesterday I dreamt about you. I hardly remember the details, just that we kept on merging into one another, I was you, you were me. Finally you somehow caught fire; I remembered that fire can be smothered with cloth, took an old coat and beat you with it. But then the metamorphoses resumed and went so far that you were no longer even there; instead I was the one on fire and I was also the one who was beating the fire with the coat. The beating didn’t help, however, and only confirmed my old fear that things like that can’t hurt a fire. Meanwhile the firemen had arrived and you were somehow saved after all. But you were different than before, ghostlike, drawn against the dark with chalk, and you fell lifeless into my arms, or perhaps you merely fainted with joy at being saved. But here the transmutability came into play: maybe I was the one falling into someone’s arms.”

Franz Kafka in a letter to Milena Jesenska

“I must confess I once envied someone very much because he was loved, well cared-for, guarded by reason and strength, and because he lay peacefully under flowers. I’m always quick to envy.”

Franz Kafka in a letter to Milena Jesenska

“His knowledge of the world was extraordinary and deep; he was himself an extraordinary and deep world.”

Milena Jesenska writing about Kafka in his obituary